13th BATTALION - 34th BATTALION A.I.F.

Private: 7036 John Sanson MIDDLETON.

Born: July 1883. Pontypridd, Glamorganshire, Wales.

Died: 26th June 1951. Naremburn, New South Wales, Australia. Death Cert:12159/1951.

Father: Stephen Middleton. (1834-1934)

Mother: Sarah Miller Middleton. nee: Flann. (1846-1895)

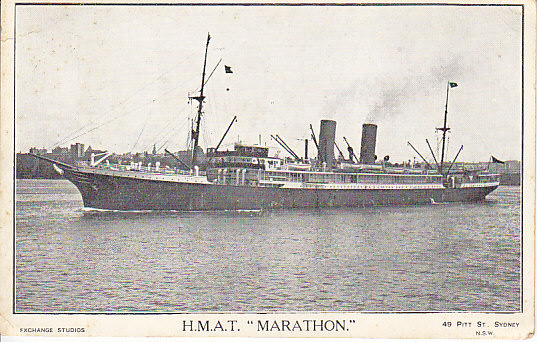

INFORMATIONJohn Sanson Middleton enlisted at the Sydney Showground with the 23rd Reinforcements, 13th Battalion AIF on the and went into camp at the Showground. The reinforcements embarked from Sydney, on board HMAT A72 "Beltana" on 25 November 1916 and disembarked at Devonport England on the 29th of January 1917. John was marched in to the 4th Training Battalion at Codford where the Reinforcements settled down to hard training, which included Route Marching, Trench Digging, Bomb Practice, Musketry and general Camp Routine.

John was admitted to the Devonport Hospital suffering from Influenza the day after arriving in Devonport while the rest of the Reinforcements were in training, John spent the next 19 days in hospital and upon his discharge on the 19th of February he was marched in to the No:1 Command Depot at Persham Downs and returned to the 4th Training Battalion the next day. john was again admitted to hospital on the 5th of March 1917 with Influenza and upon discharged he was marched in the the 12th Training Battalion in preparation for overseas deployment.

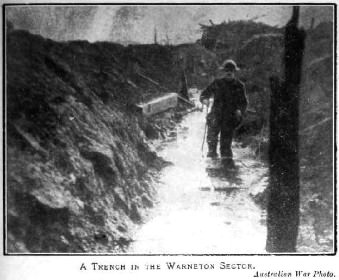

John proceeded overseas for France via Southampton on the 12th of December 1917 to reinforce the 34th Battalion AIF and was marched in at Rouelles the next day. The march over cobblestones was very tiring, notwithstanding the many route marches which had been carried out whilst in training. However, after bathing their feet and receiving treatment, as well partaking of a good meal, some spent a comfortable night. The Battalion rested here in billets and marched out on the 19th of March to join their units. John was Taken on in Strength with the 34th Battalion in the Field on the 24th of March 1918.

30th March 1918.

9:30 am: weather wet, Battalion left CACHY and marched to BOIS LE ABBE, where they bivouaced in readiness to go forward as Counter attack troops. "B" Teams were sent to BLANGY-TRONVILLE. Battalion moved up as support Battalion to 33rd Battalion AIF who were attacking on north side of BOIS DE HANGARD and LANCERS WOOD. Battalion moved West and south of CACHY when approaching BOIS DE HANGARD advanced in Artillery formation. Battalion halted just north of BOIS DE HANGARD in position of readiness to support 33rd Battalion AIF.

6:00 pm: About 6:00 pm A Company 34th Battalion was detailed to go forward to report to Commanding Officer 33rd Battalion AIF who were on left flank of attack. In moving up A Company extended into 4 lines of skirmishes and laid down with cover fire from line near 33rd Battalion Headquarters. Officer Commanding A Company Captain: Telford Graham GILDER went forward to reconnoiter 33rd Battalion's line. B Company 33rd Battalion was found to have suffered heavy casualties and enemy were still holding the top of ridge. It was therefore decided to attack enemy's position on ridge.

Shortly before 8:00pm A Company 34th Battalion moved forward in two waves each of two platoons. When 100 yards in rear of 33rd Battalion Head Quarters the 2nd wave inclined to the left and came up on the left of the leading wave and the whole Company attacked the ridge in one line. The enemy were driving out of what apparently was there Picquet Line where two Machine Guns were captured. The line extended its advance and drove the enemy out of his continuous line at the point of a bayonet, and advanced a further 50 yards at this point 7 prisoners were captured, 4 of whom actually went prisoners rage.

The number of enemy casualties was estimated at 60 killed and wounded. Machine Gun fire was very heavy from enemy lines on the left flank and was responsible for the death of 2nd Lieutenant: 1973 Reuben PARKES a very gallant officer and most of the casualties were suffered by this company. The enemy continuous trench system was then occupied for about 2 hours. In the meantime patrols were sent out to the right flank to try to establish communication with the 33rd Battalion AIF. These patrols encountered enemy posts behind our own line on this flank. Touch was eventually gained through a patrol of the 33rd Battalion under Captain: Telford Graham GILDER. On information received from Lieutenant: 916 Robert Cecil KING That it was impossible for the 33rd Battalion to push forward on to the line which the 34th Battalion were holding, it was decided to move back to the line which the 33rd Battalion had then dug in on about 250 yards to our rear.

We then dug in our men filling a gap of about 650 yards in the 33rd Battalion line apparently the enemy did not discover our tactical withdrawal until some time later at about 1:30 am, the enemy appeared on the sky line advancing in extended order. This apparent counter attack was completely broken up by our Machine Gun and Lewis Gun fire. About 3:00 am "A" Company 34th Battalion were relieved by a Survey Regiment Company then moved to CACHY. "B" Company 34th Battalion also occupied a position in 33rd Battalion line but did no actual fighting and had no casualties.

Major: Walter Arnold LeRoy FRY. took Command of Battalion the situation N.E of VILLERS BRETONNEUX at this time was rather obscure. The 12th and 17th Lancers requested the 34th Bn to throw in to stiffen up the line in the vicinity of 8 24 D and O 30 center. This request could not be acceded to as the Battalions role was counter attack. Their mobility would be gone immediately they took over the line.

4.30 pm. An order was received from Lieutenant Colonel, Henry Arthur GODDARD Temporary Commanding 9th Infantry Brigade operations that 34th Bn was to withdraw to high ground in the rear of the village. On receipt of this order the Bn was withdrawn to the high ground in vicinity of O 28 central. This position had a particularly good field of fire N and N.W. of VILLERS BRETONNEUX.

4.45 pm. A second order was received for Battalion to withdraw to high ground in rear of village South of Railway Line but as the village had not been taken by the enemy and the cavalry were still operating N and N.E of the village it was decided that before withdrawing the Bn the C.O. Major: Walter Arnold LeRoy FRY. would see the acting Brigadier.

5.10 pm. Instructions were received from Lieutenant Colonel, Henry Arthur GODDARD C.O. Operations through Lieutenant Colonel. Leslie James MORSHEAD. that as the position was rather obscure on the left flank in vicinity of U 36 G and C the 34th Bn was to establish a line and connect the right flank with the 33rd Bn and the left flank with the Cavalry. After reconnecting the lime it was decided by Major: Walter Arnold LeRoy FRY. in consultation with Lieutenant Colonel. Leslie James MORSHEAD and the C.O. of the 17th Lancers that the Cavalry would hold the line with their right flank on road P 25 C 70 30.

The 33rd Bn would side slip to the North, and take up a position with their left flank on road exclusive at P 25 c 70 30 and their right flank at P 31 A 65 11, and the 34th Bn would take over from P 31 a 65 11 to Railway Line via 30 98 inclusive. The elements of the 35th Bn N of Railway Line were to side slip to the south side of the Railway Line and were to hold in conjunction with 36th Bn from Railway Line via V1 A 30 98 to vicinity of U 6 central. This operation was successfully completed by 8.55 pm.

At this time the 34th Bn held the line as follows:-"D" Coy on right from Railway Line inclusive ay V1 A 30 98 to P 31 C 90 77. "C" Coy from P 31 C 90 77. "A" Coy in close support to "D" Coy. "B" Coy in close support to "C" Coy.

Battalion Headquarters established with 33rd and 35th Battalions at O 36 D 20 60. 10.00 pm Brigadier decided that as the enemy had established a line on high ground in vicinity of Railway Bridge V1 G 67 and a strong Machine Gun post at the bridge from which he could enplane our line N of the Railway, and command approaches to the village, it was essential this position should be cleaned up and the 34th Bn was detailed to attack and capture Railway Bridge in V 1 G 67, consolidate a line 250 yards in front of the Brigade, the 36th, 35th and 33rd Battalions moving their line forward to conform to 34th Bn Zero time was set for 1.00 am.

This operation was entirely successful, the 34th Bn capturing 12 Machine Guns, 1 Officer and 22 other ranks of enemy taken prisoner. Slight opposition was met South of the Railway a strong party of the enemy encounter on the Railway and North of us. In the advance our own Lewis Guns were fired from the hip, and had a considerable moral effect on the enemy. The line was consolidated and the remainder of the night passed quietly.

5th April 1918.

6.00 am. Bright and clear. Great aerial activity, very little seen of the enemy planes. 2.00 pm. Enemy heavily bombarded our line from Railway Line V 1 G 90 50 to P 31 D with whizz bangs 4.2's and 5.9,s. Fortunately trenches built on previous night were very narrow and being spaced in Platoon posts were difficult to hit. Only a few casualties resulted. The ground was extremely flat and it was impossible to have any communication with front line during hours of daylight. 34th Bn was relieved by 17th Bn AIF on the night of 5/6. Relief was complete by 11.30 pm. On completion of relief marched to posts of readiness in O 34 a. Cover was dug in side of hill, but as a particularly cold, wet night, the men could not be made comfortable. The role of the Battalion in tis position was counter Attack.

4th-5th April 1918

The First VILLERS-BRETONNEUX The Strength of the 9th Infantry Brigade was about 2,250 but their casualties during the 2 days of fighting numbered 30 Officers and 635 men either killed in action or missing.

9th Infantry Brigade Casualties.4th-5th April 1918

| 33rd Battalion. AIF |

3 Officers |

82 Other ranks |

| 34th Battalion. AIF |

5 Officers |

120 Other ranks |

| 35th Battalion. AIF |

9 Officers |

282 Other ranks (including 44 missing) |

| 36th Battalion. AIF |

12 Officers |

133 Other ranks (including 1 missing) |

| 9th Machine Gun Company. AIF |

1 Officer |

18 Other ranks (including 4 missing) |

On the night 5th/6th April the Battalion was relieved by the 17th Battalion and marched to Bois d'Aquenne and dug in the side of a ridge for cover, the night being very cold and wet. The morning of 6th April was bright and clear and there was great activity in the air. Fights were frequent, with as many as 30 Planes on each side fighting it out. The Transport coming up with the rations was getting a particularly warm time from the heavy shelling. Whilst here dry socks and underclothing were obtained for the men from Villers Brettonneux. Despite the bad weather and heavy fighting during the last 12 days, the men were in fine fettle and their moral was excellent. On the 7th April the men moved into Villers Brettonneux and billeted in cellars in the vicinity of the Cross Roads.

The enemy continued to shell the town during the afternoon and night and rain again began to fall. About noon on 8th April the enemy put over an exceptionally heavy Barrage, but the men being housed in cellars, very little damage was done. On the night of the 9th April the Battalion relieved the 19th battalion in the Front Line, in the vicinity of Bois d'Hangard. The enemy had Strong Posts out in front, which was protected by barb wire in the stubble. The ground in front was absolutely flat, giving a good Field of Fire. During the next day our area, as well as Cachy and Hangard Villages, was heavily shelled. The following three days, except for some Machine gun Fire, were normally quiet.

John was treated on the 11th of April and transferred to the 39th General Hospital at Abbeville after surviving the last 3 weeks in the front line. He was transferred to Harve on the 14th of April before being invalided to England in the 18th June suffering from Premature Senility and was marched in the the No:2 Command Depot at Weymouth for repatriation to Australia. He embarked for Australia onboard HMAT "Medic" on the 24th August and disembarked on the 13th October 1918. John was discharged from the AIF on the 12th November 1918.

RSSLA Badge B9592 issued to John Sanson Middleton who served with the 34th Battalion AIF was acquired in March 2015 and is now in the Harrower Collection.

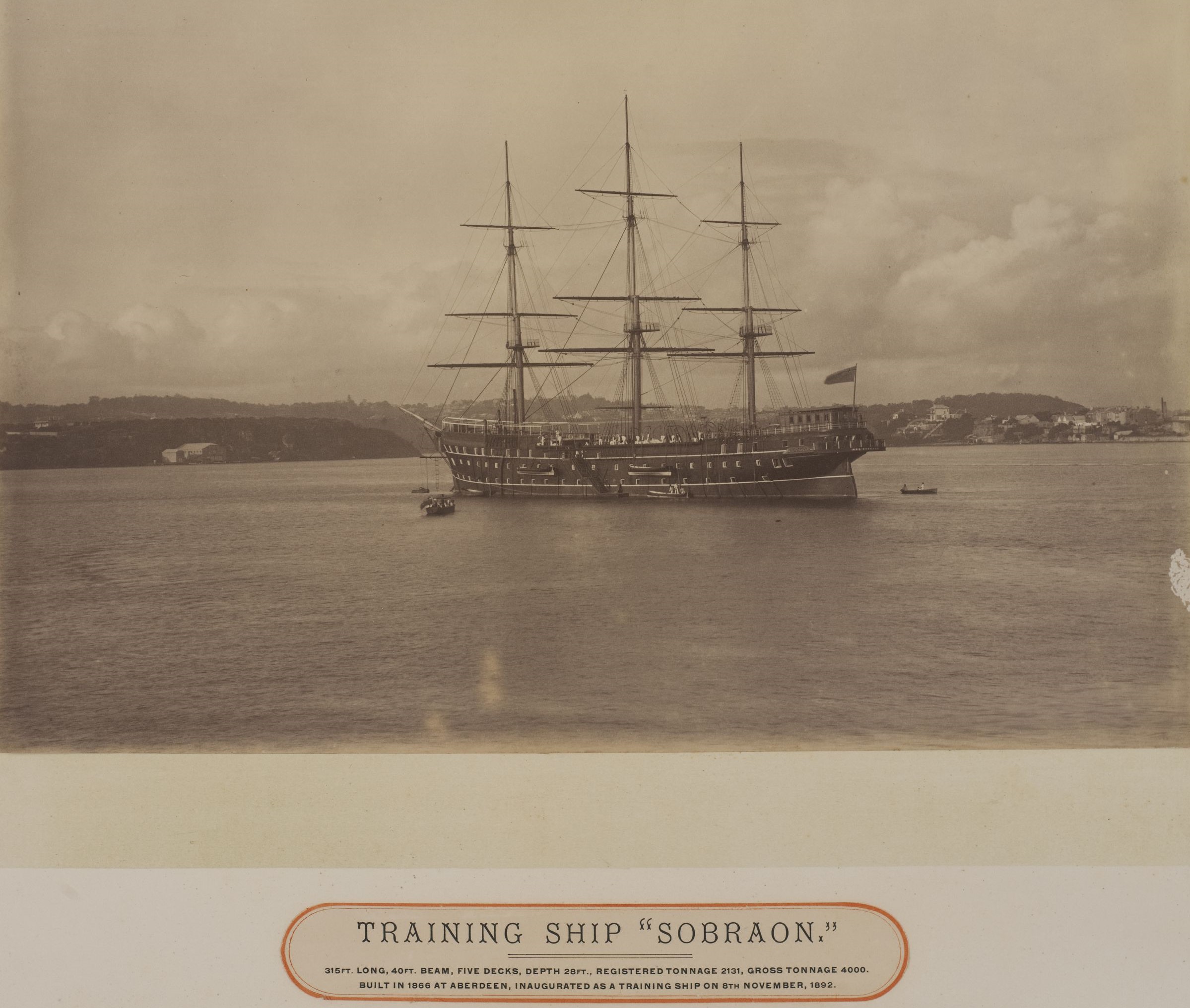

Family InformationJohn was born in 1883 in the Coal Mining Rhondda Valley County. John was a single 33 year old Marine Engineer from 27a Grovesenor Street, Neutral Bay upon enlistment. His father Stephen Middleton lived at Winnie Street, Neutral Bay, N.S.W.

RSSLA Badge B9592 issued to John Sanson Middleton who served with the 34th Battalion AIF was acquired in March 2015 and is now in the Harrower Collection.

Family InformationJohn was born in 1883 in the Coal Mining Rhondda Valley County. John was a single 33 year old Marine Engineer from 27a Grovesenor Street, Neutral Bay upon enlistment. His father Stephen Middleton lived at Winnie Street, Neutral Bay, N.S.W.

MINERS STRIKE 19101910: Cambrian Combine miners strike and Tonypandy riot A short history of a strike by miners in South Wales in 1910 which led to a series of confrontations between workers and police, culminating in what became popularly known as the Tonypandy Riot.

MINERS STRIKE 19101910: Cambrian Combine miners strike and Tonypandy riot A short history of a strike by miners in South Wales in 1910 which led to a series of confrontations between workers and police, culminating in what became popularly known as the Tonypandy Riot.

The strike marked one of the few occasions in British history that troops have been deployed against striking workers. The strike began on August 1, 1910, when miners employed by the Naval Colliery Company at the Ely Pit in the town of Penygraig arrived at work to find lockout notices attached to the entrances of the mine. The company and pit made up part of the Cambrian Combine, a business network founded in 1906 of all of the mining companies in South Wales formed to regulate prices and wages while still allowing each individual company to operate independently. The months that followed became one of the bitterest disputes the miners of South Wales were ever to be engaged in, and one that would affect every miner who worked in a Cambrian Combine pit. The build up to the strike had begun the year previously, when the management of the Ely Pit had taken the decision to open up a new seam and have it mined by 80 men for a trial period in order to determine its output. The miners of the pit were employed on the basis of piecework, pay being dependent on the amount of coal extracted by each individual worker. If a miner failed to reach a certain amount, the company would give an allowance to the miner in question to make up his pay to the minimum that was required in order to live. Given the nature of this pay system, the test period of the new seam to determine it's output and to allow the company to set a wage per ton of coal extracted would also determine the amount the company was likely to have to pay miners who would work on the seam in future.

Some months into the test period of the new seam, the company began to accuse the men working on it of deliberately working slowly in order to raise the amount that would be paid per ton of coal once the seam was in production and the miners were working at their "normal pace". The miners argued that this was not the case, telling the company that the seam was particularly difficult to work with many "abnormal places". When the test period was over, a wage was set for the workers on the new seam that was far lower than what could be considered a living wage, and they demanded an increase. The company had recently also been cutting the allowance given to miners, making the money made from piecework alone practically impossible to live on. Angered by the resistance they were meeting from the miners over the new wages, the owners posted lockout notices on August 1. The lockout applied not just to the 80 miners working on the new seam, but all 800 miners employed at the pit. Soon after they had been met by the lockout notices, the miners called the strike, and were soon joined by miners from two other pits owned by the Naval Colliery Company as well as others from several other collieries in South Wales who voted to strike several days later. A conference of the South Wales Miners Federation (SWMF) was held on September 16. 248 delegates attended, representing the 147,000 miners of the Miners' Federation of Great Britain and the decision to support the strikers was made. Several token pay increases still far below what could be considered a minimum living wage were offered by the mine owners and were all rejected by the workers, who were soon to be joined on strike by 30,000 other miners on November 1, the day the strike called by the SWMF officially began.

Picketing began at all of the collieries that made up the Cambrian Combine in the area and on November 7, all pits affected by the strike were being picketed by their workers. A crowd of thousands marched though the Rhondda valley with miners filling the streets, gathering at pitheads and in many cases, entering their collieries to extinguish boiler fires and stop ventilation fans, making the mine unworkable to any scabs who had stayed in. Production was halted by workers in all pits except one in the town of Llwynypia, which had been transformed into a near fortress by its manager, who had at his disposal a large amount of police who had been drafted in by the Chief Constable of Glamorgan as soon as the strike had begun. Production at the colliery at Llwynypia was being kept running by about 60 scabs who had kept the machinery in the pit running with the aid of the 100 policemen from Swansea, Bristol and Cardiff preventing entry by the strikers. The colliery was important to both the strikers and the mine owners, being that it housed the electric generator and pumping station that kept that mines free of water, thus keeping the colliery operational. The owners were desperate to keep it out of the hands of the strikers, being dependent on the contingent of policemen guarding the power station building at the site to be able to maintain a minimal level of production.

By 10.30 pm on the evening of November 7, thousands of strikers had encircled the pit at Llwynypia, determined to gain entry and shut the colliery down. Unable to get inside, they began to throw stones at the policemen guarding the power station and heavy fighting soon ensued between the two groups, with some miners breaking off sections of wooden fencing to use as weapons. Some hours later, and after being subjected to repeated baton charges by the police, the strikers were pushed away from the colliery and into the square at nearby Tonypandy where they were further dispersed by waiting police. Sometime during the fighting in the square, the police authorities, worried about losing control of the situation telegraphed Tidworth barracks for army reinforcements, which were promised to arrive the next morning. However, the unapproved reinforcements had been stopped by order of the then home secretary, Winston Churchill, before they had even crossed into Wales. When contacted by an angry police captain, Churchill, fearful of political criticism he would come under if he deployed troops against the miners, maintained that they should only be used as a last resort, but said that he would keep them on standby nonetheless. Instead he sent several hundred policemen from London, including about 70 mounted police.

The strikers returned to the pit at Llwynypia on November 8, and again heavy fighting between police and miners began. Some two hours into the fighting, mounted police succeeded in dispersing the miners into two groups, one of which headed for the middle of Llwynypia, the other heading again for Tonypandy. Fighting intensified in Tonypandy as the mounted police failed to disperse miners in the town, who began to smash shop windows. Homes in Tonypandy were left untouched by the angry miners, and after several hours of running battles with the police, Churchill telegrammed General MacReady, commander of the troops on standby with the message, "As the situation appears to have become more serious you should if the Chief Constable or Local Authority desire it move all the cavalry into the district without delay". Several hundred extra police from London were also promised, but by the time they arrived the next day the fighting had ended with about 500 miners injured as well as about 80 policemen. Samuel Rhys, a miner who sustained head injuries from a policeman's baton later died of his injuries. This series of events over the 7th and 8th of November in Tonypandy made up what became popularly known as the "Tonypandy Riot".

Thirteen miners were arrested and prosecuted for their part in the unrest and the authorities, fearing more trouble, transformed Tonypandy and the surrounding area into a near military camp. The trial lasted for several days and on each day 10,000 men marched through the valley and held mass meetings outside the town in support of their friends in jail, despite the streets being filled with soldiers and policemen. Eventually, several of the miners standing trial were sentenced to prison terms ranging from two to six weeks, while the others were fined and released.

Sporadic fighting continued for several more weeks and on November 22 a group of picketing miners were forced by soldiers with bayonets drawn onto a hillside near Penygraig, where they fought alongside the women of the community for several hours with troops and police. A local newspaper running a story on the event commented on the actions of the women:

"Women joined with the men in the unequal combat, and displayed a total disregard of personal danger which was as admirable as it was foolhardy. But these Amazons of the coalfield resorted to other and more effective methods. From the bedroom windows came showers of boiling water, which fell unerringly on the heads of police, while in one case a piece of bedroom ware found its billet on the skull of a Metropolitan policeman."

Major disturbances were also reported at the town of Blaenclydach in April 1911, where heavy fighting took over the centre of the town with shops being looted as they had been in Tonypandy. The strike however, ended several months later with the miners, feeling the strain of being without pay for so long, being forced to accept a small pay increase. They returned to the pits in early September, exactly a year after the strike had begun.

Tonypaddy Riot 1910

When Coal was King in Wales’ Rhondda ValleyScarcely an hours drive west of the pristine villages, prosperous cottage gardens, and sylvan landscapes of the cotswolds lies the southern Welsh county of mid-Glamorgan. Throngs of touring coaches, camera-wielding photojournalists, and well-heeled tourists don't come here. These are the valleys of the Rhondda. Fanning out above the Welsh capital of Cardiff, these valleys are the coal fields of South Wales, narrow glens snaking their way south to north, from the Bristol Channel coast toward the Brecon Beacons. Every few miles up and down the hills lie the skeletal remains of a pit head, rusting silently, majestic.

When Coal was King in Wales’ Rhondda ValleyScarcely an hours drive west of the pristine villages, prosperous cottage gardens, and sylvan landscapes of the cotswolds lies the southern Welsh county of mid-Glamorgan. Throngs of touring coaches, camera-wielding photojournalists, and well-heeled tourists don't come here. These are the valleys of the Rhondda. Fanning out above the Welsh capital of Cardiff, these valleys are the coal fields of South Wales, narrow glens snaking their way south to north, from the Bristol Channel coast toward the Brecon Beacons. Every few miles up and down the hills lie the skeletal remains of a pit head, rusting silently, majestic.

Though in popular parlance the name Rhondda has become synonymous with the mining district, the Rhondda itself is a dual-pronged valley rising north of Pontypridd. The Little Rhondda threads its way from Trehafod north to Maerdy, where the road runs over the hills to Aberdare. The Great Rhondda branches west to Treorchy and Treherdert, then winds north to meet the Head of the Valleys Road at Hirwaun. The people here just call them The Valleys. For more than a century, high quality, smokeless coal was extracted from the earth here. Collieries dotted the valleys, and tens of thousands of men made their livelihood cutting coal from the rich seams that ran from several feet to more than a quarter mile under the surface. This huge economic engine built the industrial port cities of Cardiff and Newport, and fueled the British navy from the later years of Victoria almost until the Second World War. Today the coal mines are silent, unprofitable in the modern economy. Though the pits have closed, however, the people remain in populous, serpentine towns lining the vales.

Life in the valleys has always been hard. During the winter, a collier never saw the sun except on Sunday, going into the pits before daybreak and emerging again after dark. Boys followed their fathers down in their early teens. With little cash and no modern conveniences, women made home and hearth for large families in two-room-up, two-room-down stone row-houses without garden or lawn. The mines yielded a death, on average, every six hours, and a serious injury every 12 minutes. In Senghynydd at the head of the Aber Valley, local historian Basil Philips recounts the story of the deep pit explosion of 1913, when 434 men and boys in this village of less than 5,000 met their deaths in the greatest colliery disaster in British history. His own father was in the mine that day.

Philips tells how the mining communities were built. As a pit was sunk, it drew men off the land, swapping the bleak agrarian life in the hardscrabble Welsh hills for the steady cash wages of the mine. As hard as the life might have been, it was an enviable step up from subsistence farming. A man looked for four things coming to work in the pits, Philips recalls. A roof over his familys head, a chapel, a mens choir, and a rugby team. While life has inevitably changed here in South Wales, the legacy is easy to see. The terraced houses are still home, though it is hard to find a block where several of them are not adorned with For Sale signs.

The dissenting chapels, Baptist, Methodist, Congregational, and Presbyterian, certainly punctuated every neighbourhood. Today, most of the chapels are as silent as the mines. Many sit derelict or converted to other uses in the secularism of late-20th-century Britain. Fewer than three per cent of the Welsh people now attend. This remnant keeps alive an important part of the valleys history, a dissenting gospel, and many of the grand Welsh hymns for which the region is renowned. The justly acclaimed male voice choirs of Wales remain. In fact, Senghenydd itself is home to one of the best, the Aber Valley Male Voice Choir. Every valley and village has its own choir. Their music continues to be one of the great defining cultural institutions of Wales; opera choruses and Welsh hymns, folk songs and show music. As well as maintaining active concert schedules, most of the men’s choirs are happy to welcome visitors to their rehearsals.

As to rugby, it is the national sport. Girls and boys pick up the game early in instructional leagues, and the great players are national folk heroes. Wales proudly hosted the quadrennial Rugby World Cup in 1999. In the sprawling valley towns, signs of economic depression and need may abound next to an immaculately maintained, flood-lit rugby pitch. Life in the valleys is still hard. The pit closures through the 80s brought massive unemployment to an already depressed region. Vast amounts of investment capital poured into the region from elsewhere in Britain, the European Community, the United States, and Japan. Though new factories have risen along the Head of the Valleys Road and across the jagged southern end, unemployment remains very high in some places.

Despite this story of hard industrial life and general economic depression, the people of the valleys are warm, good-humoured, resilient, and hospitable. Visitors fortunate enough to discover the valleys find an open welcome, a unique culture, and a great deal of interest. As Wales is a bilingual principality, of course, that friendly greeting could come in either English or Welsh. The only living Celtic language, and the oldest living European language, Welsh is visible on highway signs, in shop windows, and in print. Many schoolchildren in the Rhondda area attend schools where Welsh is the language of instruction.

The market town of Pontypridd lies in the centre of the region and calls itself ‘Gateway to the Valleys. The Historical Centre in the heart of Pontypridd exhibits the social and cultural history of the town, and doubles as the Tourist Information Centre. It is located in a former chapel. The magnificent pipe organ, still used for recitals, is the one feature that remains of the buildings chapel years. It was once the instrument of John Hughes, who composed the classic hymn Cym Rhondda, still sung throughout the world as Guide Me, O Thou Great Jehovah.

Just a few miles up the road at Trehafod, the Lewis Merthyr Colliery has found new life as the Rhondda Heritage Park. Here among the rusting relics of busier days, the unique industrial heritage and way of life is kept alive. In multimedia and reconstructions of village life, the Heritage Park tells the history of the Rhondda. Former colliers, who worked these pits for years, lead visitors underground to experience working life in the mine during the 1950s.

As dramatic and dominating as the story of coal may be, of course, the regions history goes back long before commercial mining. At Nelson, Llancaiach Fawr is a 17th-century manor house. This award-winning living history museum brings to life the Civil War in Wales, as the servants of Colonel Edward Prichard await a visit from King Charles in 1645. Costumed interpreters do a superb job of introducing gentry life in 17th-century Wales as well as the grim history of conflict between the King and Parliament of the 1640s.

Half a dozen miles to the south, the prosperous market town of Caerphilly had already been around for centuries. It sprang up in the shadow of Caerphilly Castle, the largest castle in Wales. Built in the 13th century by the Norman lord Red Gilbert de Clare, the fortress stands on three artificial islands in a 30-acre lake. Its usefulness as a fortification is long past, but the castle still dominates the town. Local folks take the mammoth castle and its unique display of medieval siege engines quite for granted. Their greater interest is fishing in the lake. Just across the street, the Caerphilly Visitor Centre not only provides tourist information, but exhibits local history and offers Welsh crafts, gifts, and a ready source for the famous white Caerphilly cheese.

The hills are greener now around here than they were when Richard Llewellyn described them in his famous, heart-warming novel of the coal fields, How Green Was My Valley. They are greener than they were a generation ago. The mountains of coal slag are now swaddled with vegetation. Stands of farmed evergreens run along many of the ridges. Still, there is no pretending that the valleys are a beautiful place, or that they will ever rival the Yorkshire Dales or the Cotswolds for the devotion of visitors, infusion of tourist spending, and creeping gentrification. Unfortunately, those seeking the pastoral Britain of popular imagination will have to look elsewhere.

The power and attraction of the Valleys lie in the warmth of her people and in an identity forged over centuries: in her homes and chapels, on the playing fields, and in the strong magical voices of her mens choirs raised in Welsh anthems like Calon Lan:

British Heritage

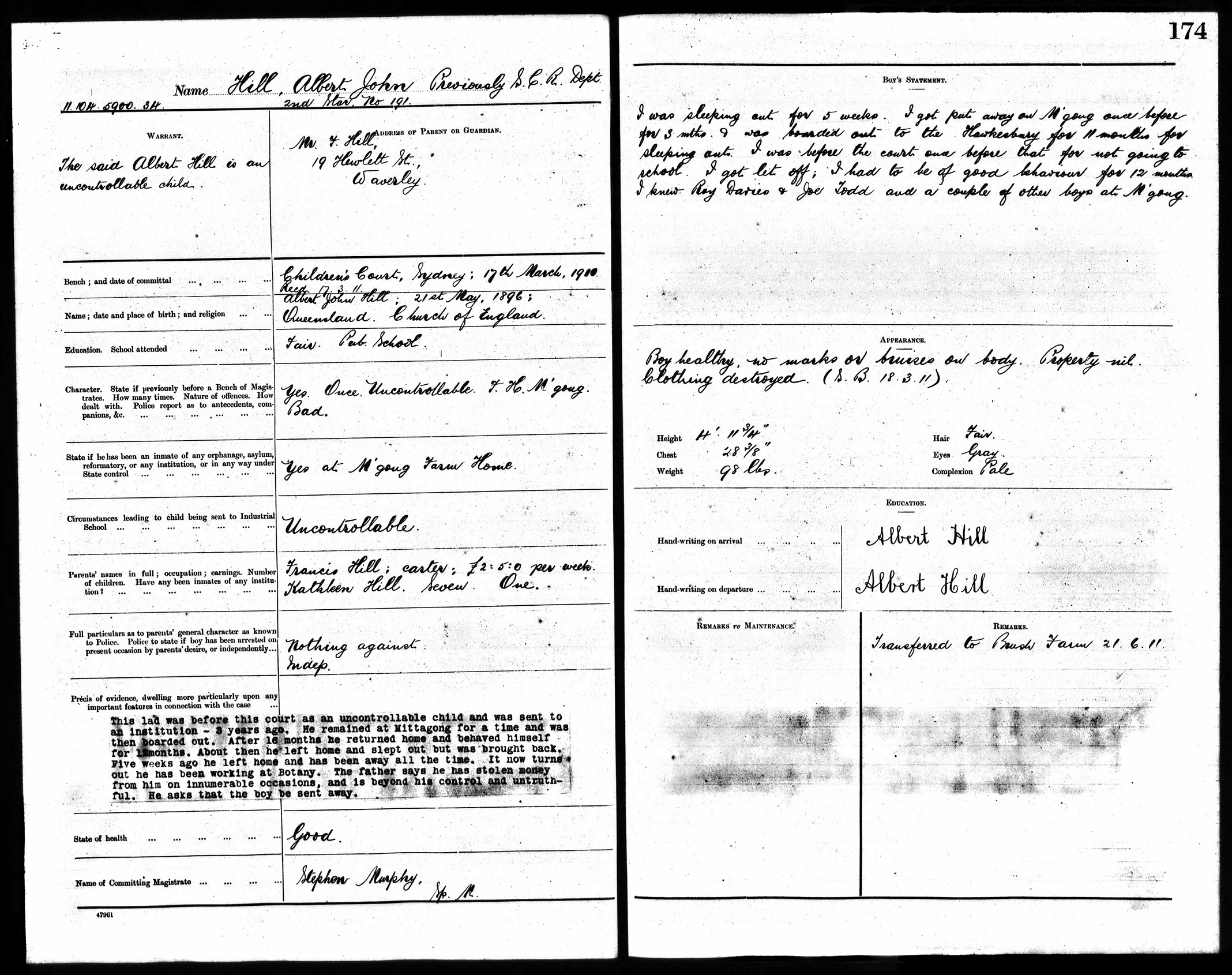

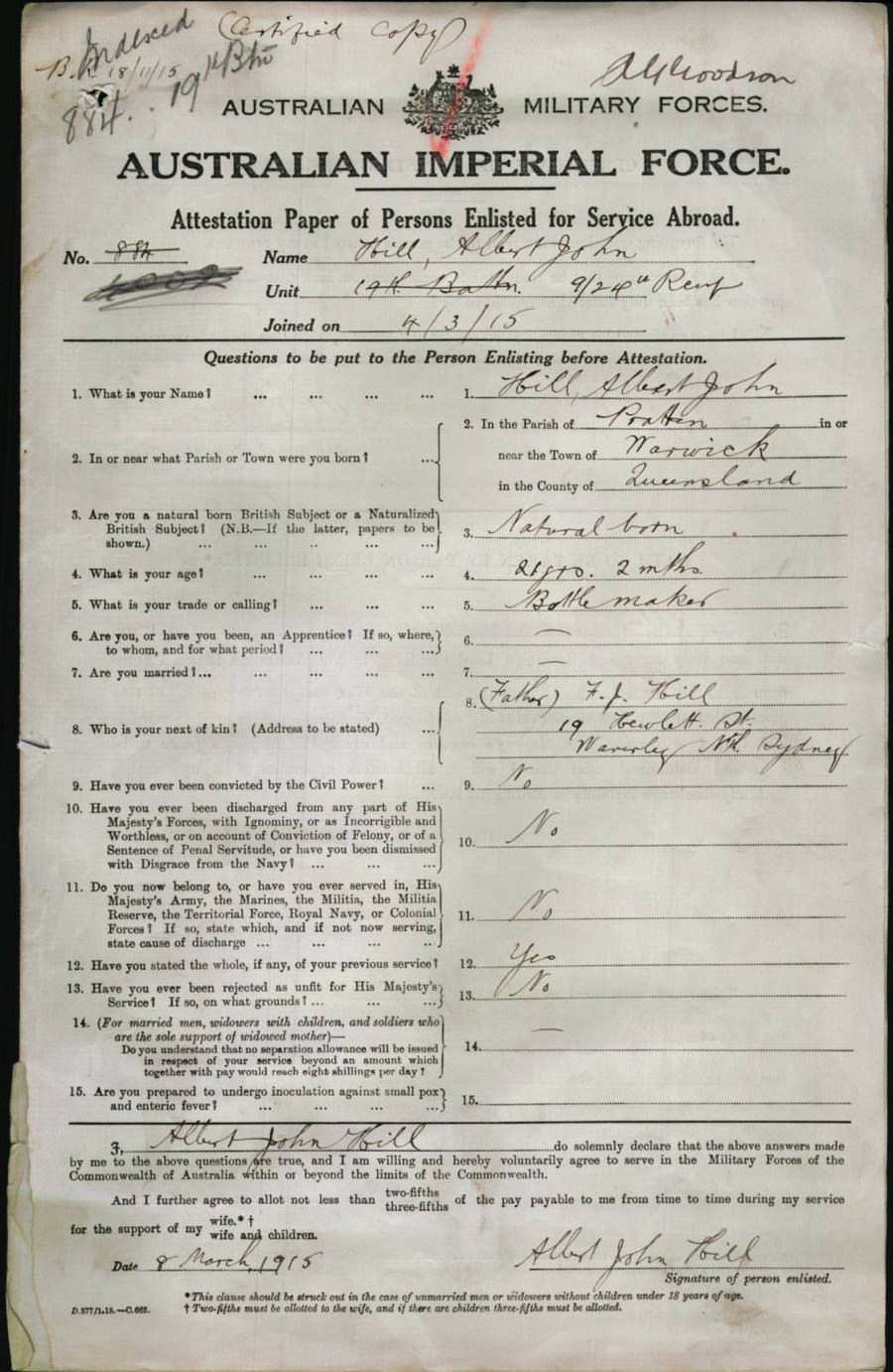

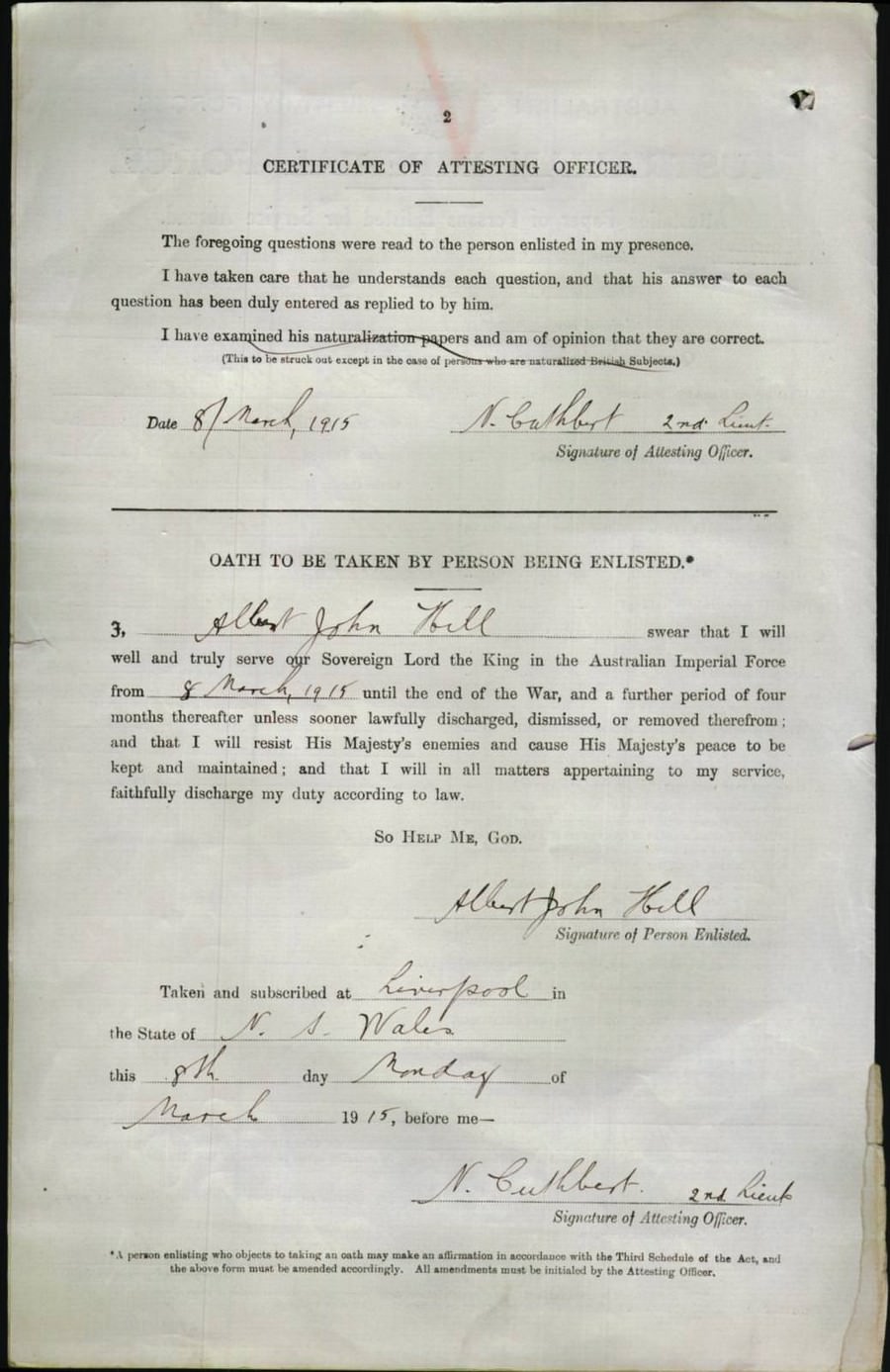

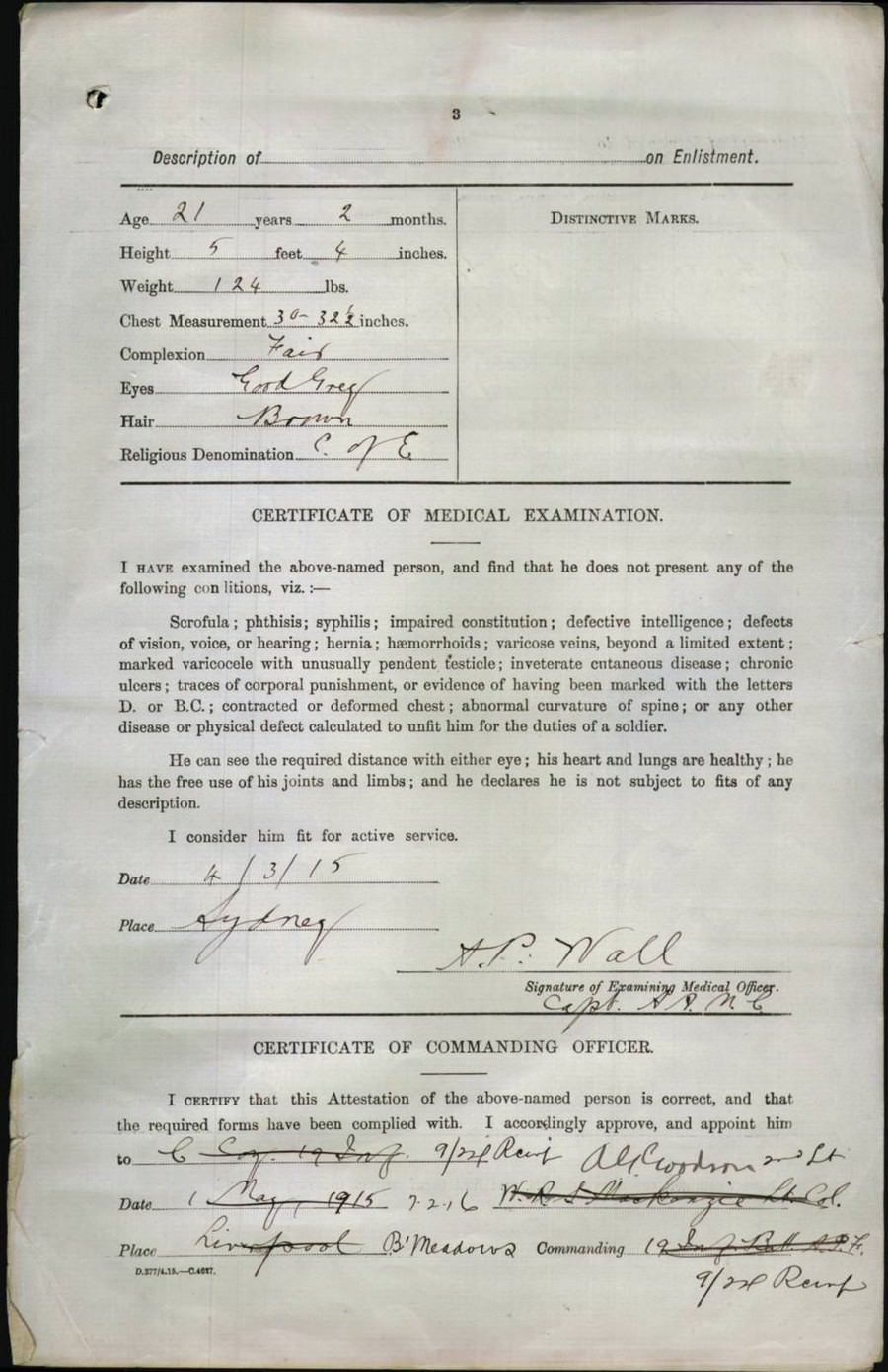

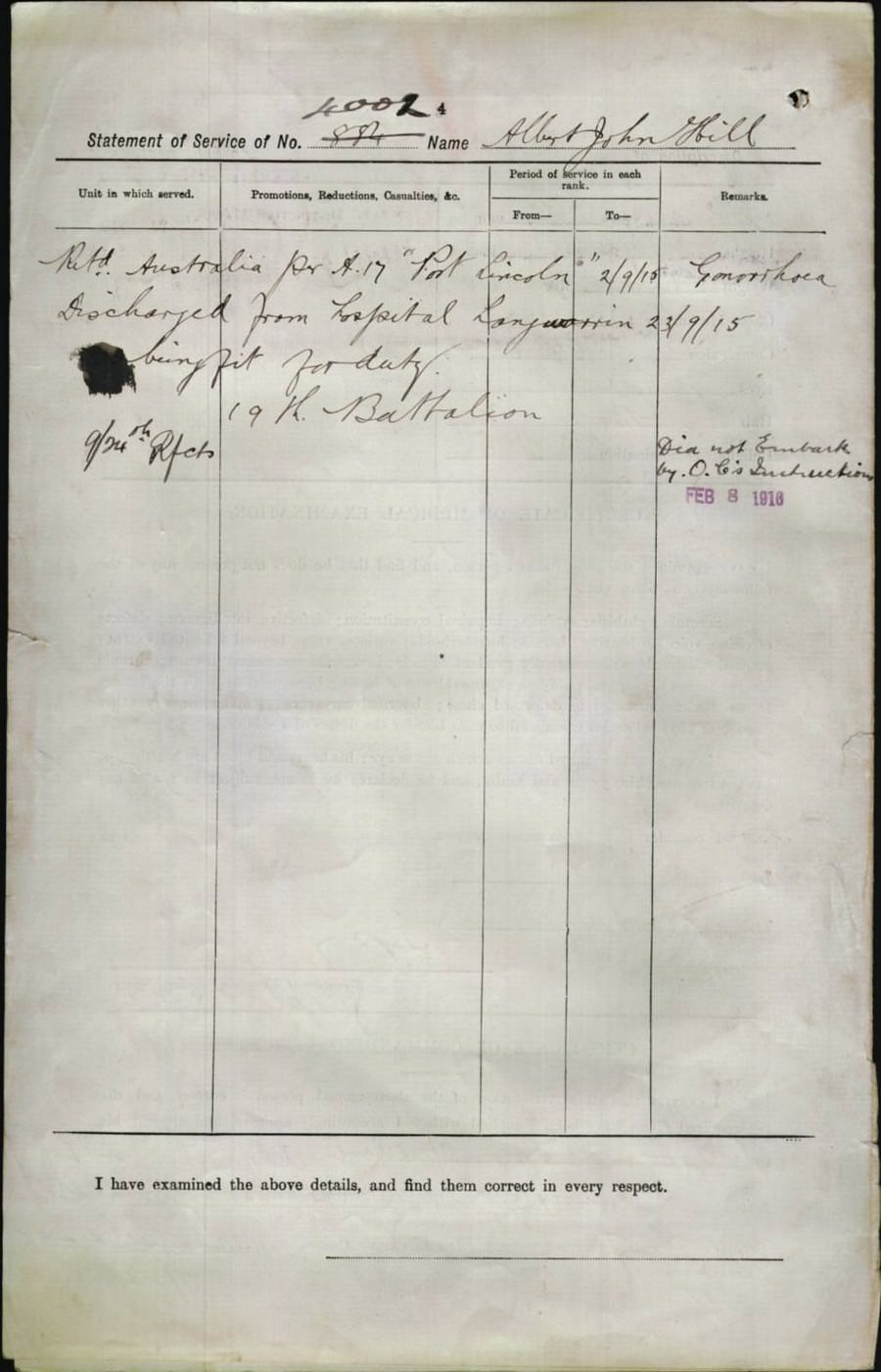

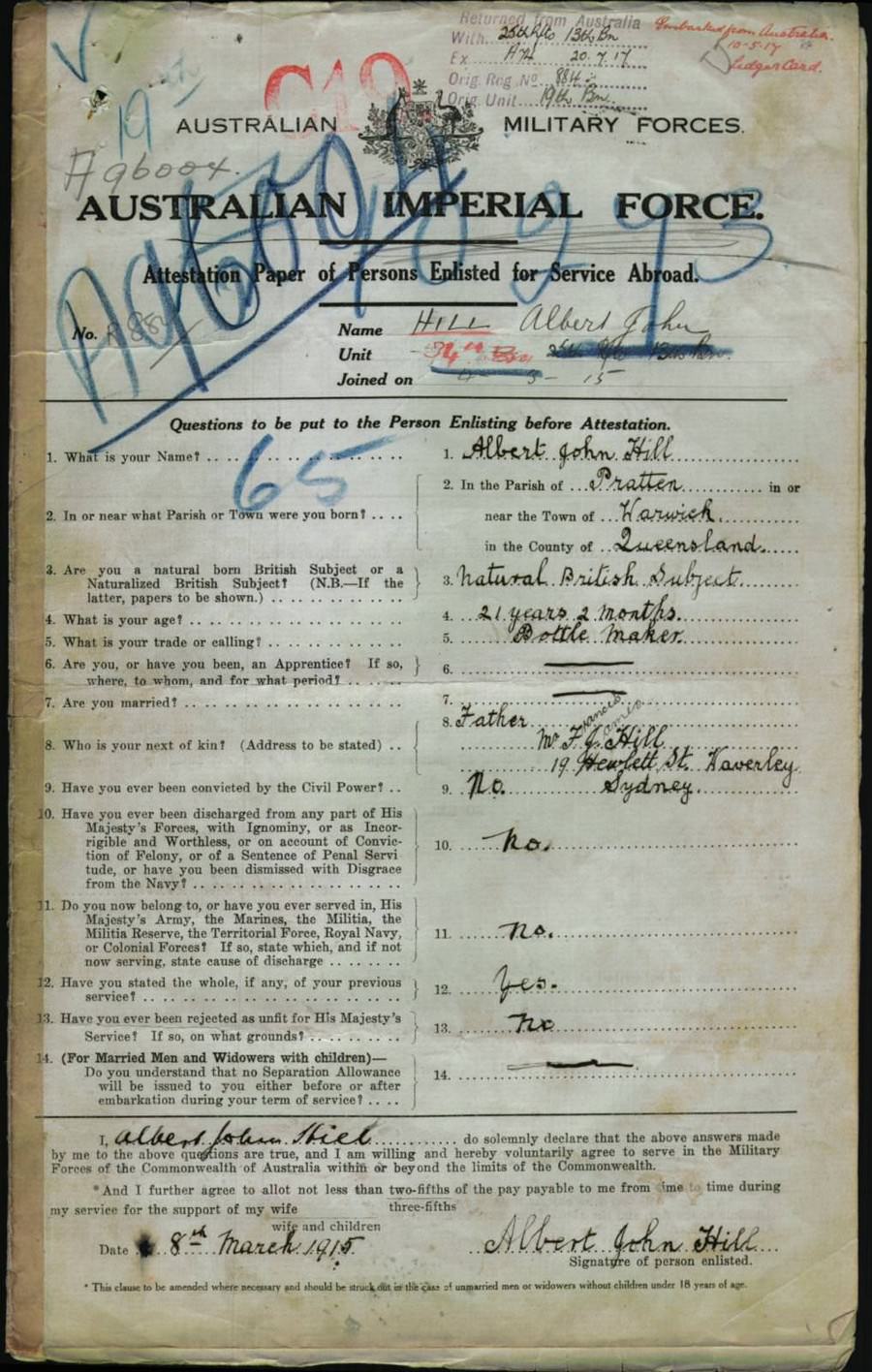

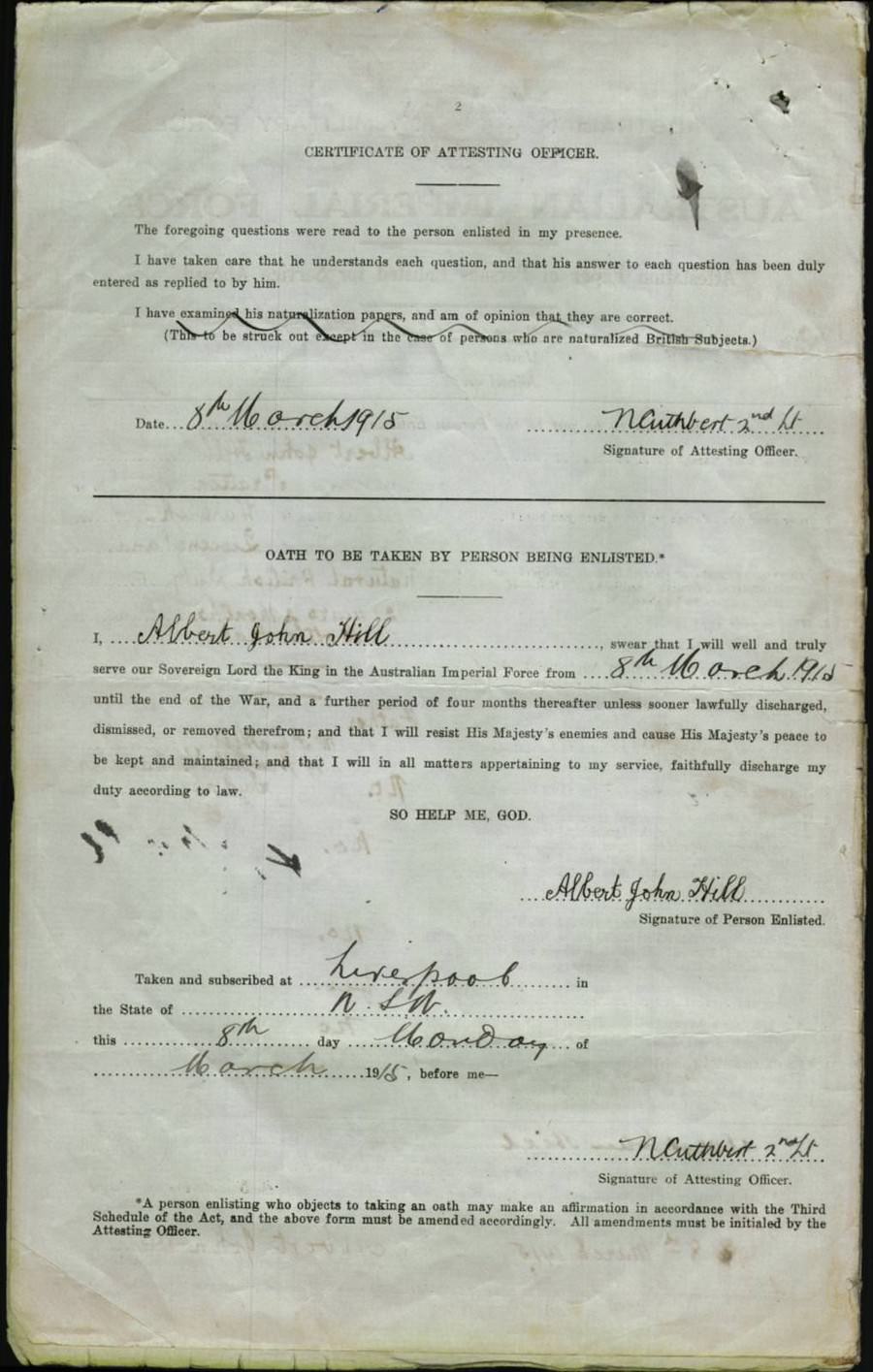

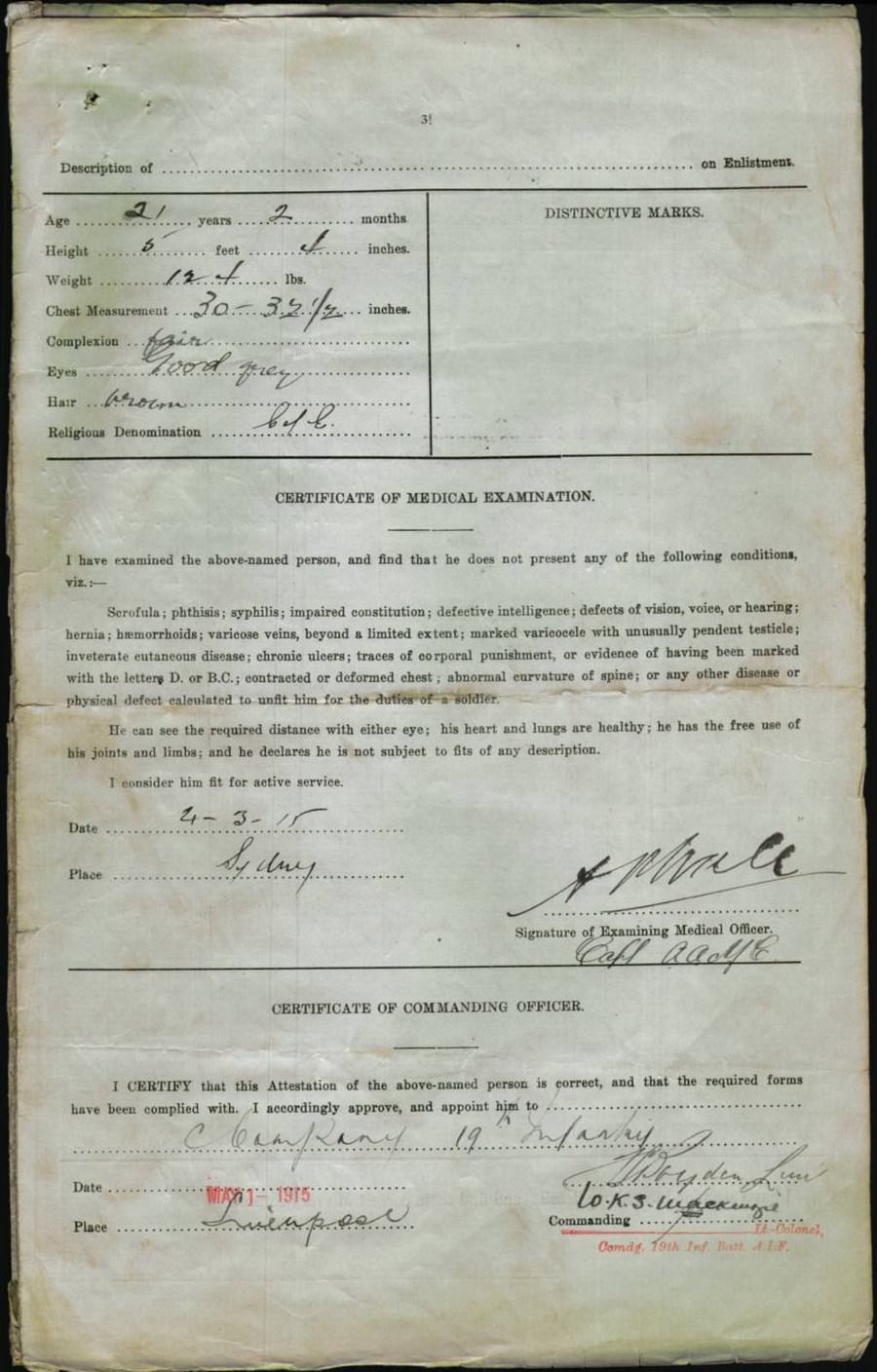

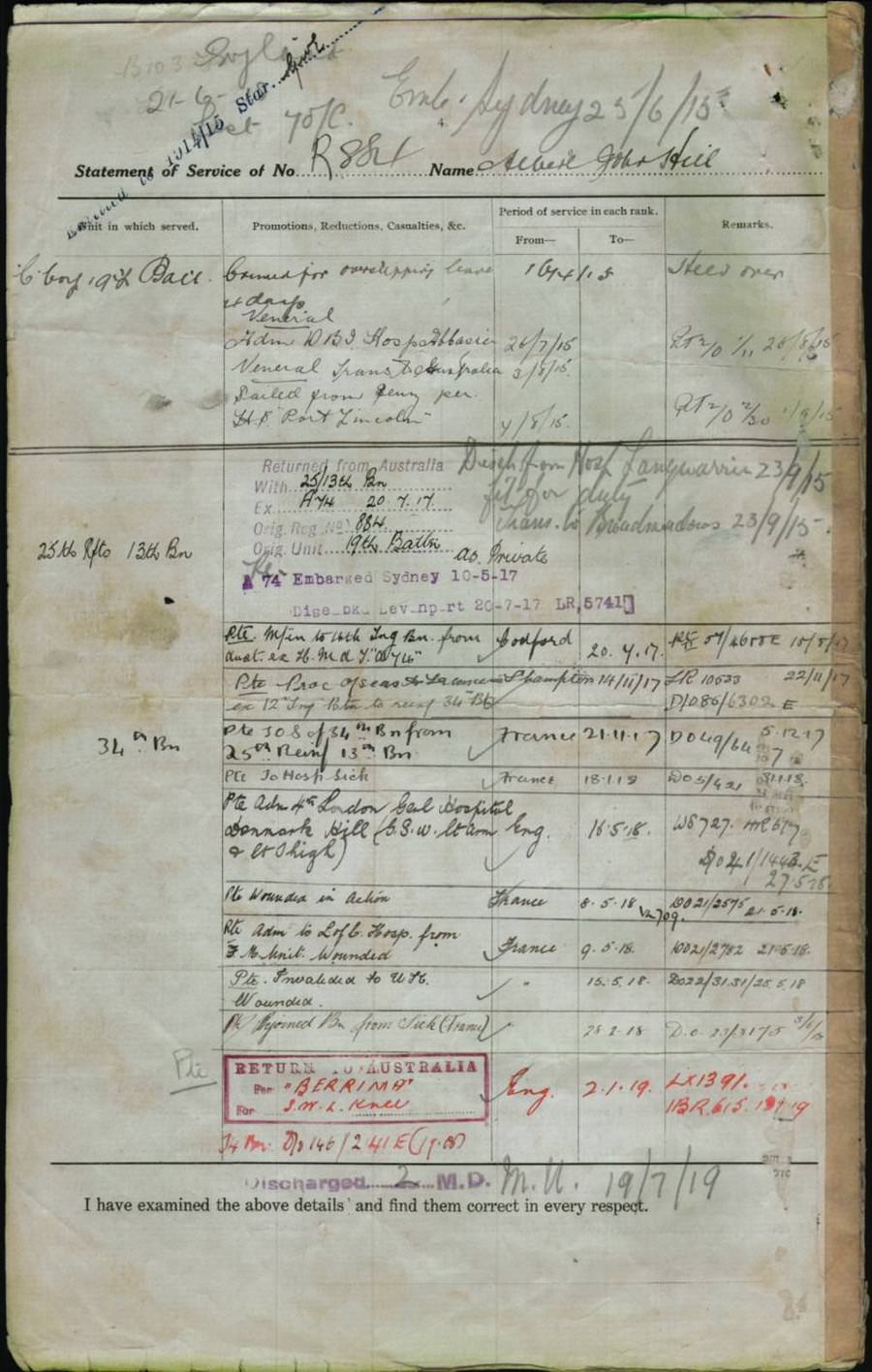

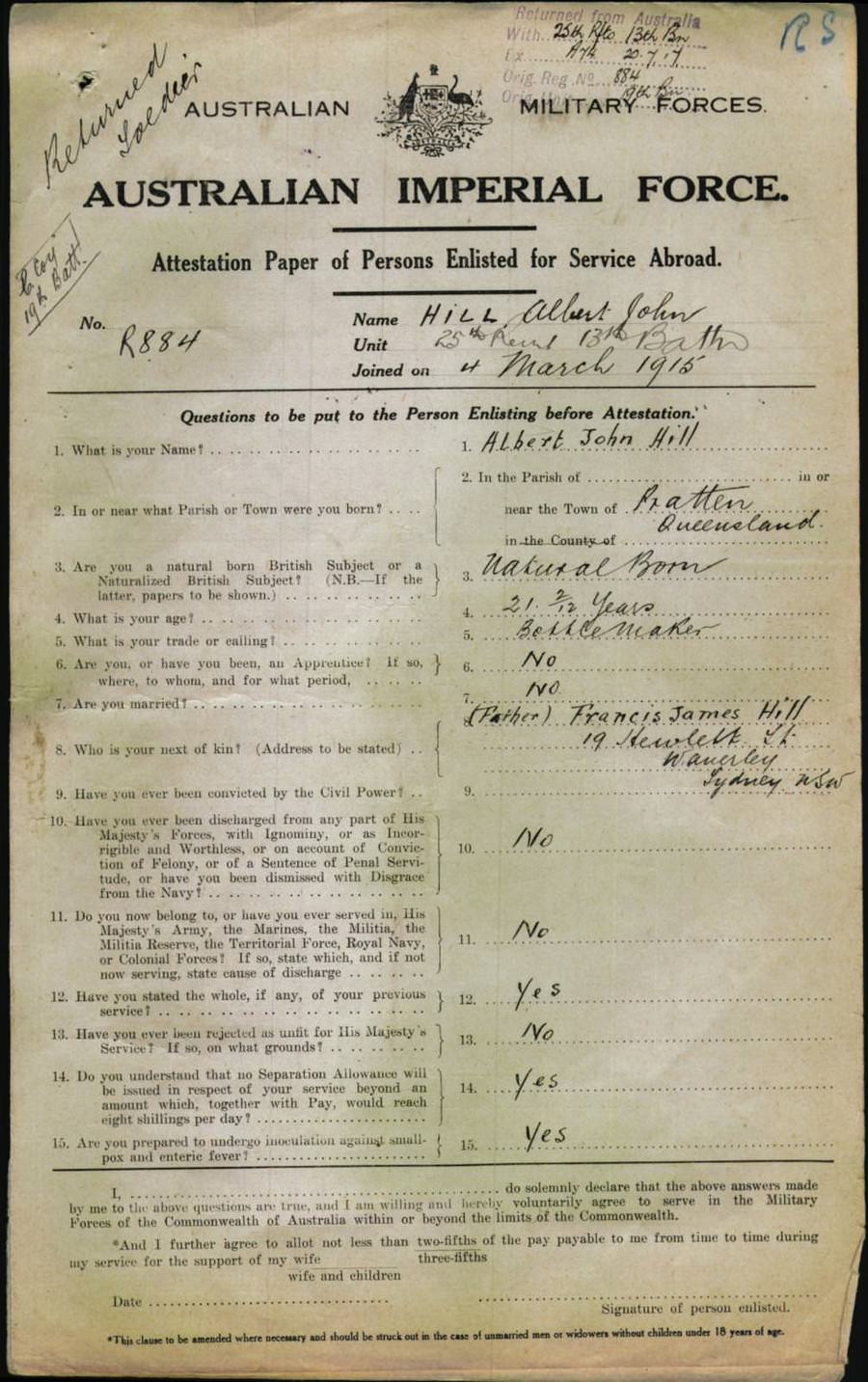

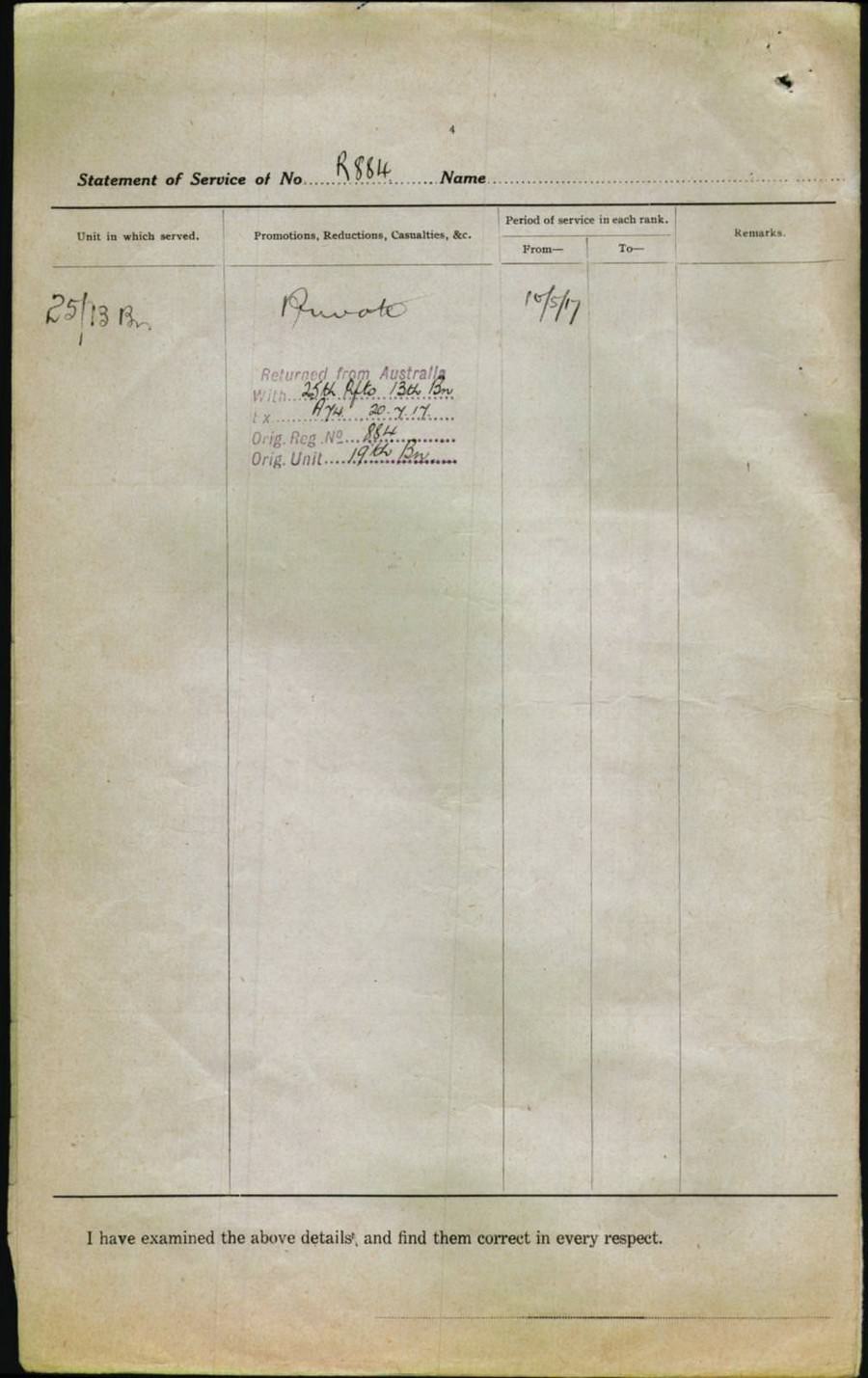

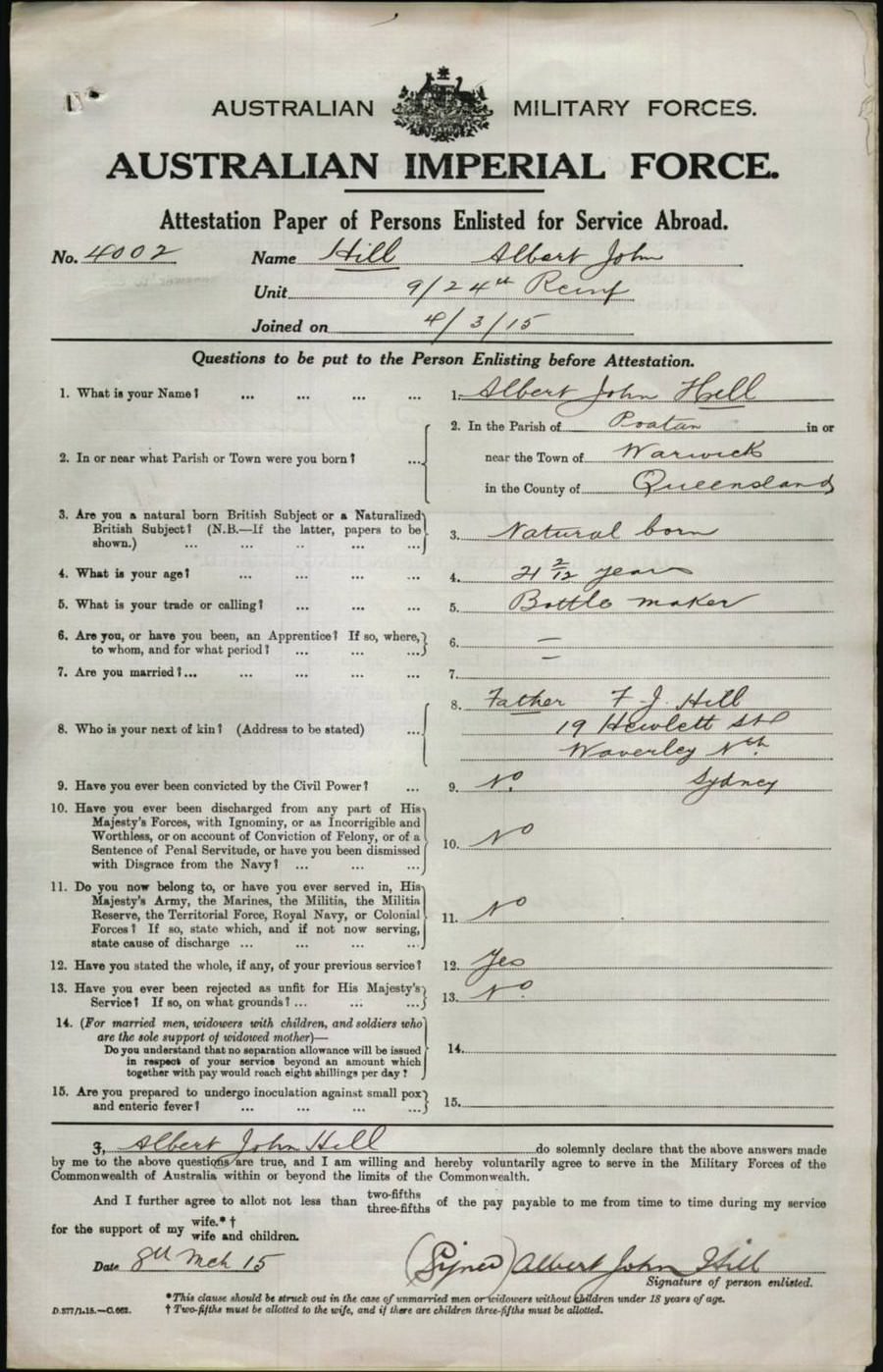

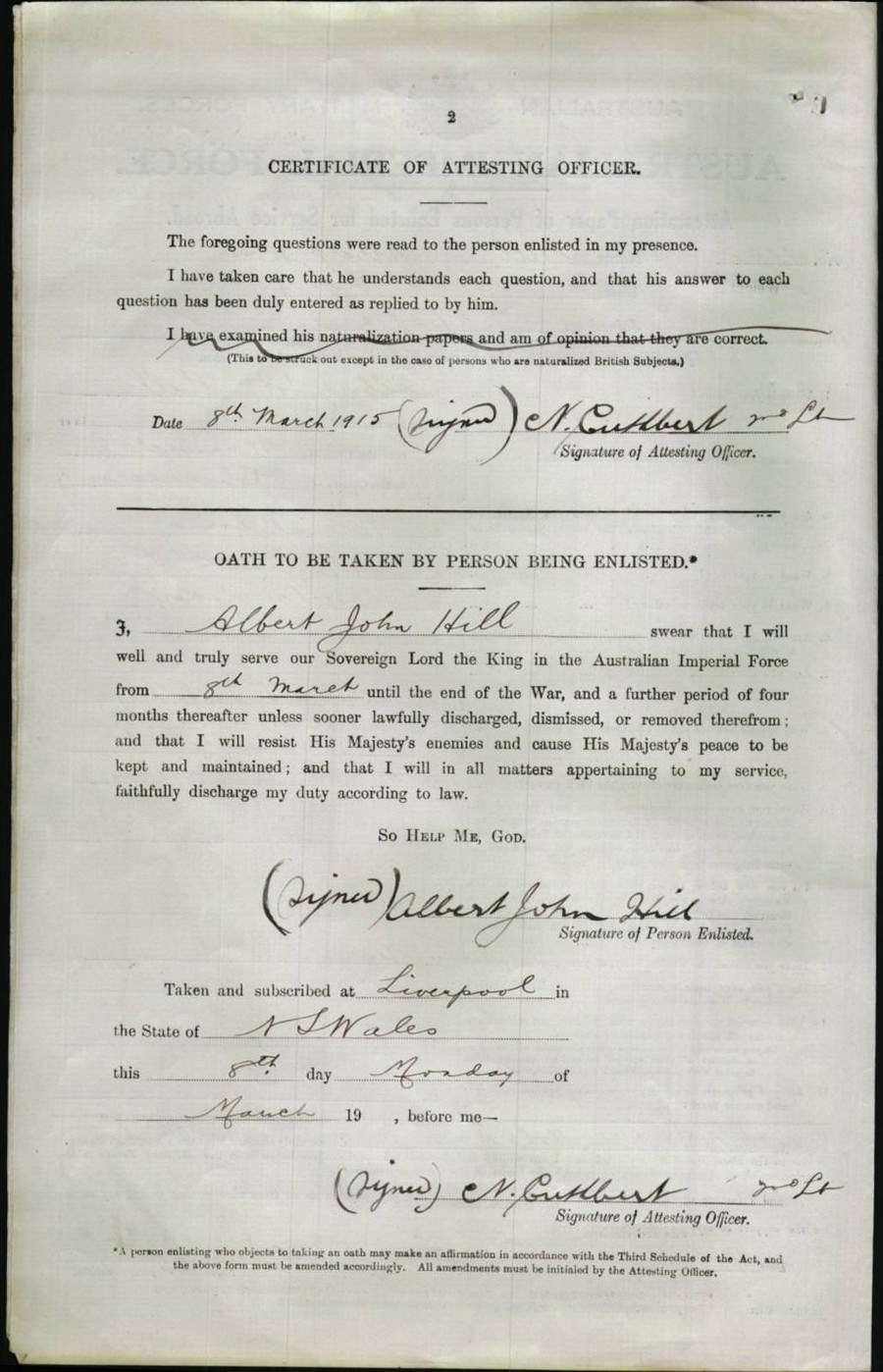

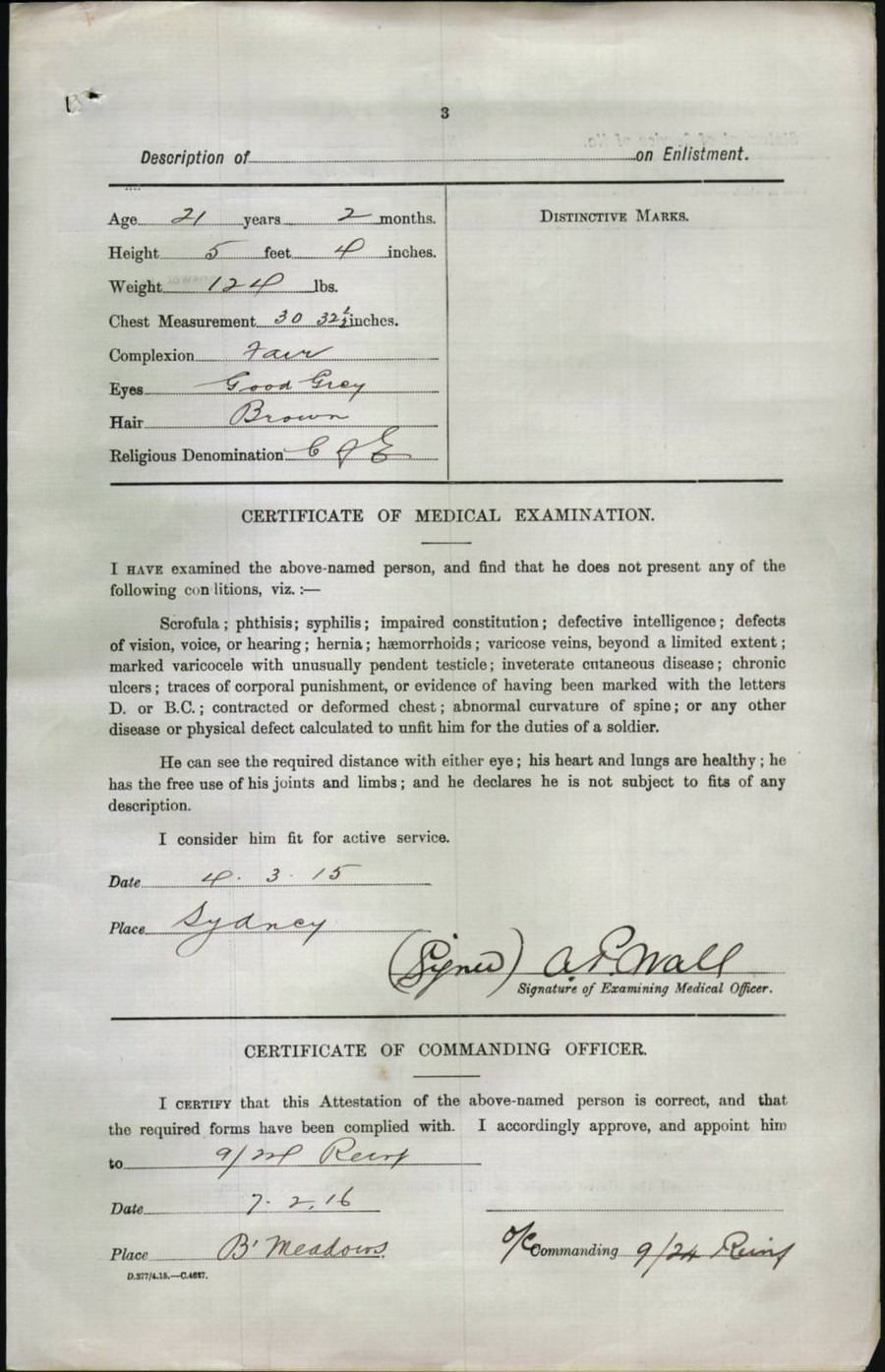

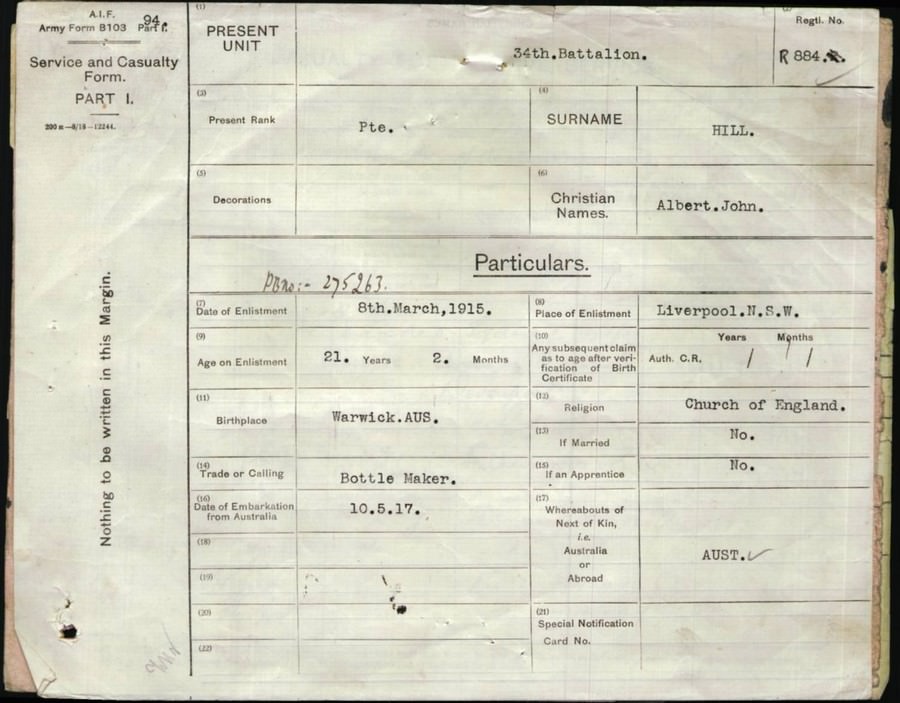

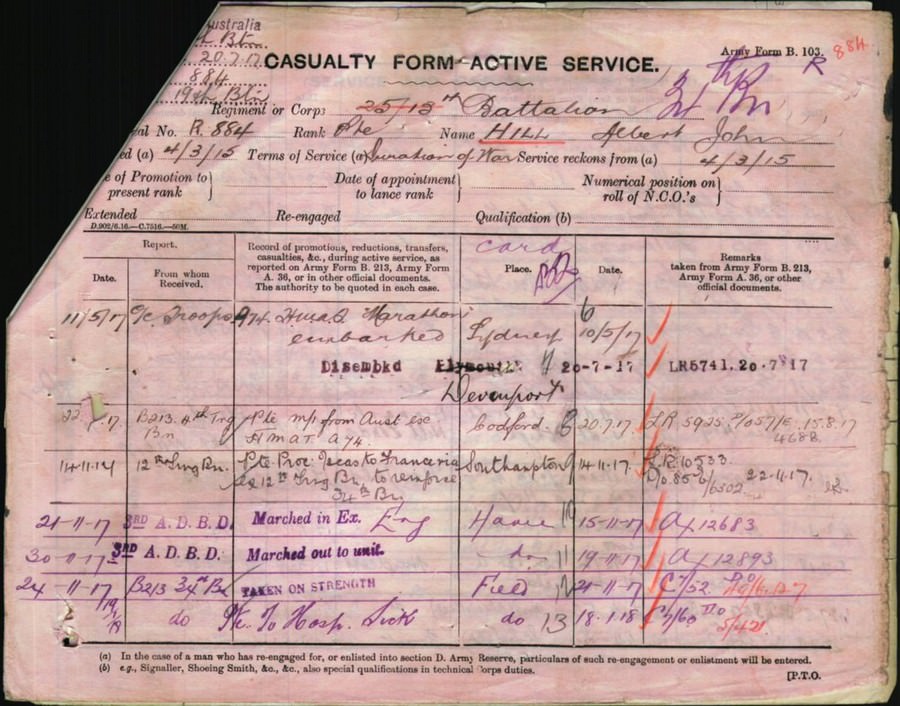

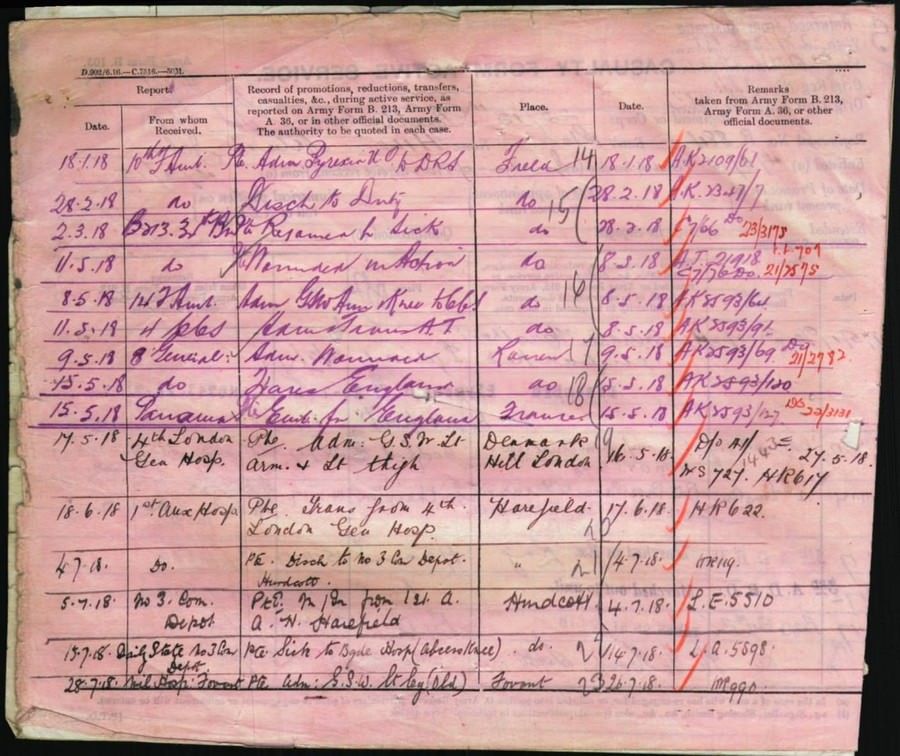

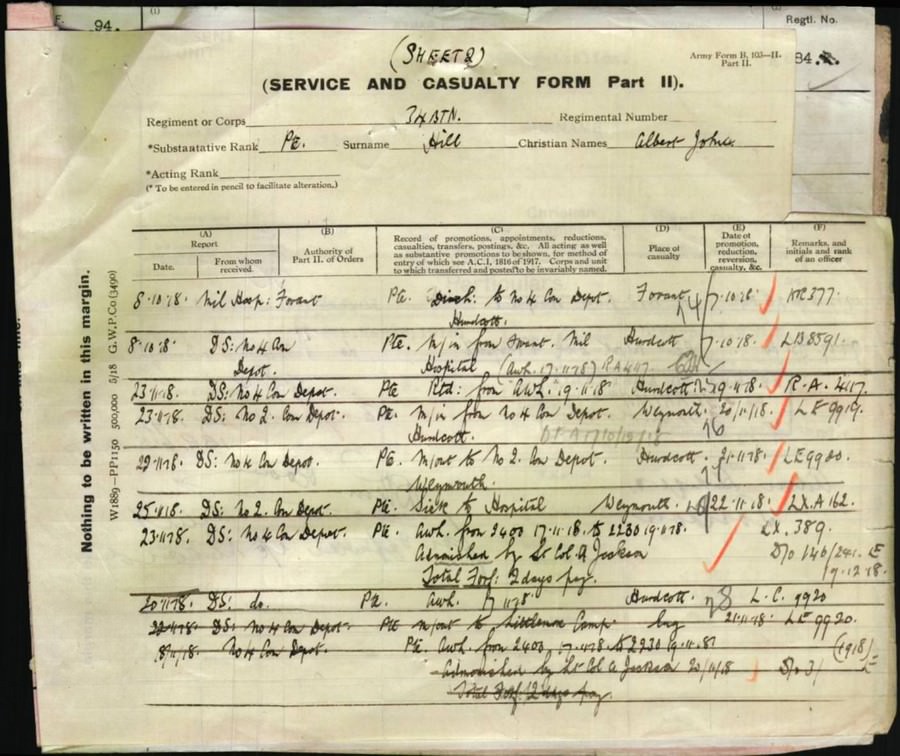

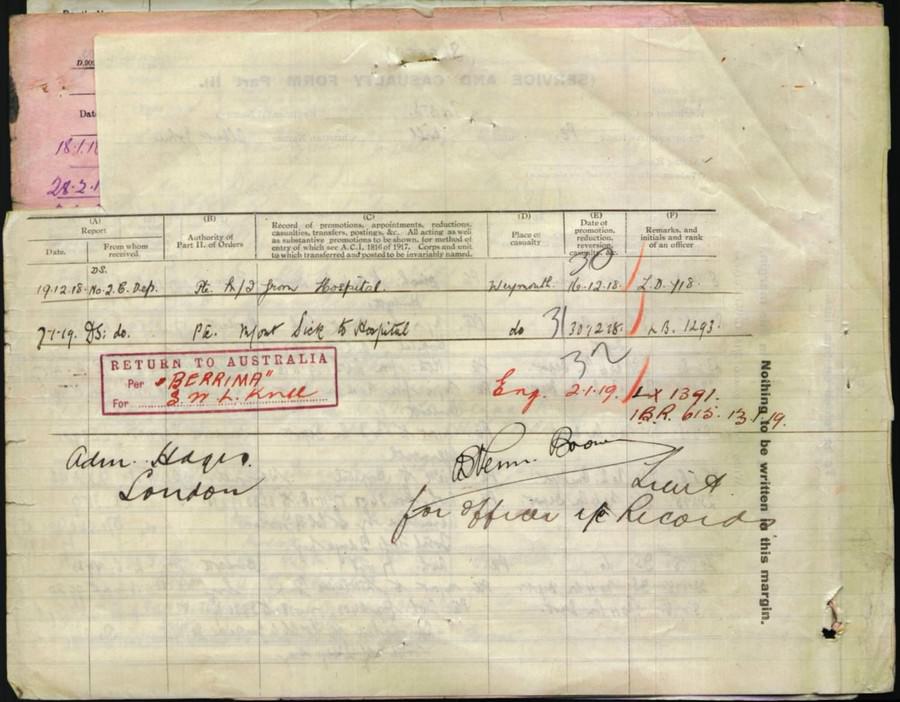

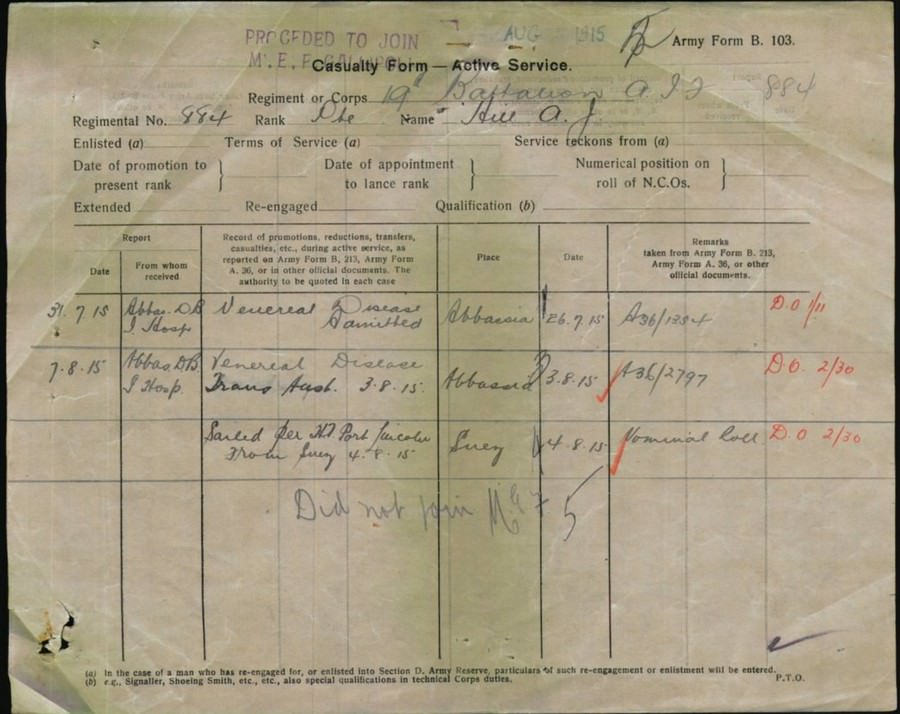

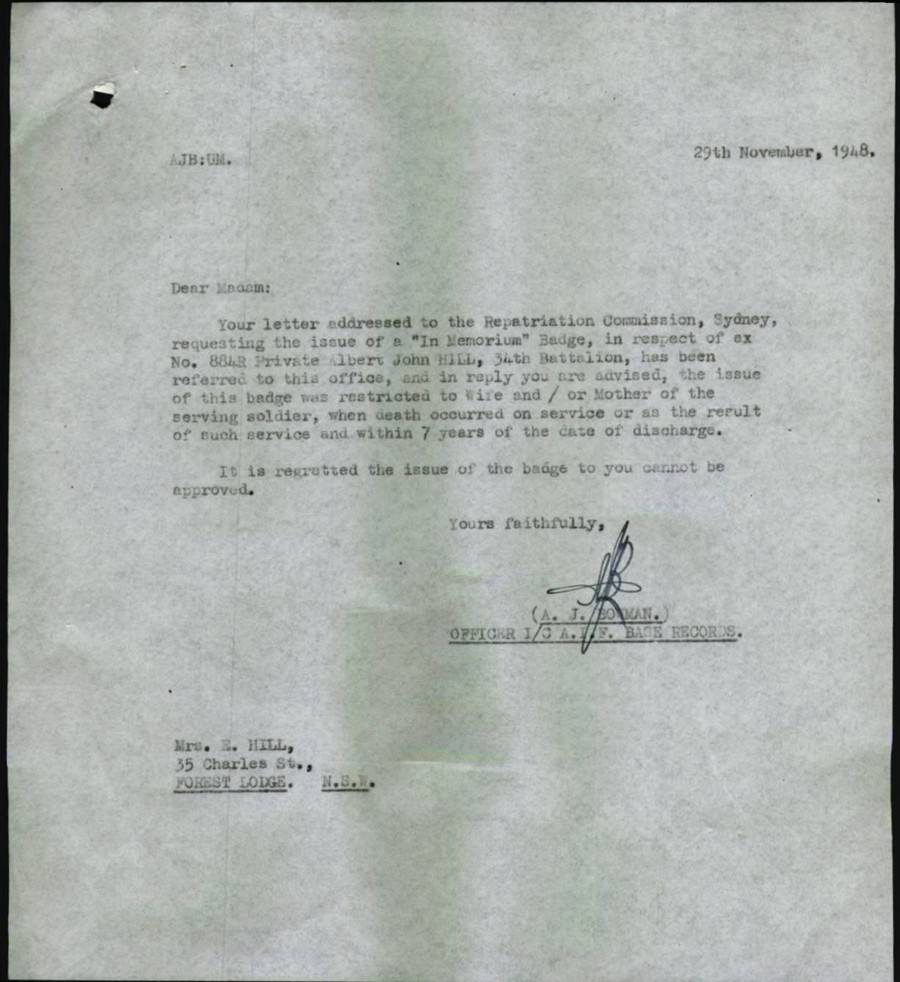

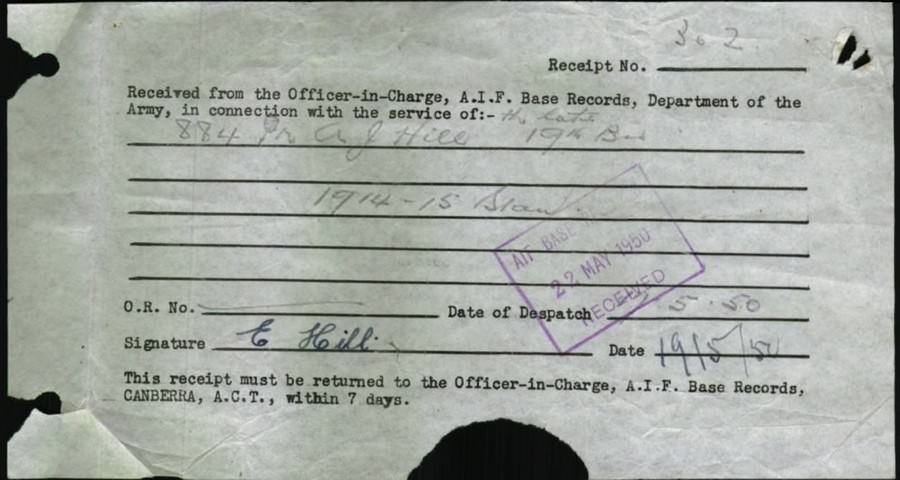

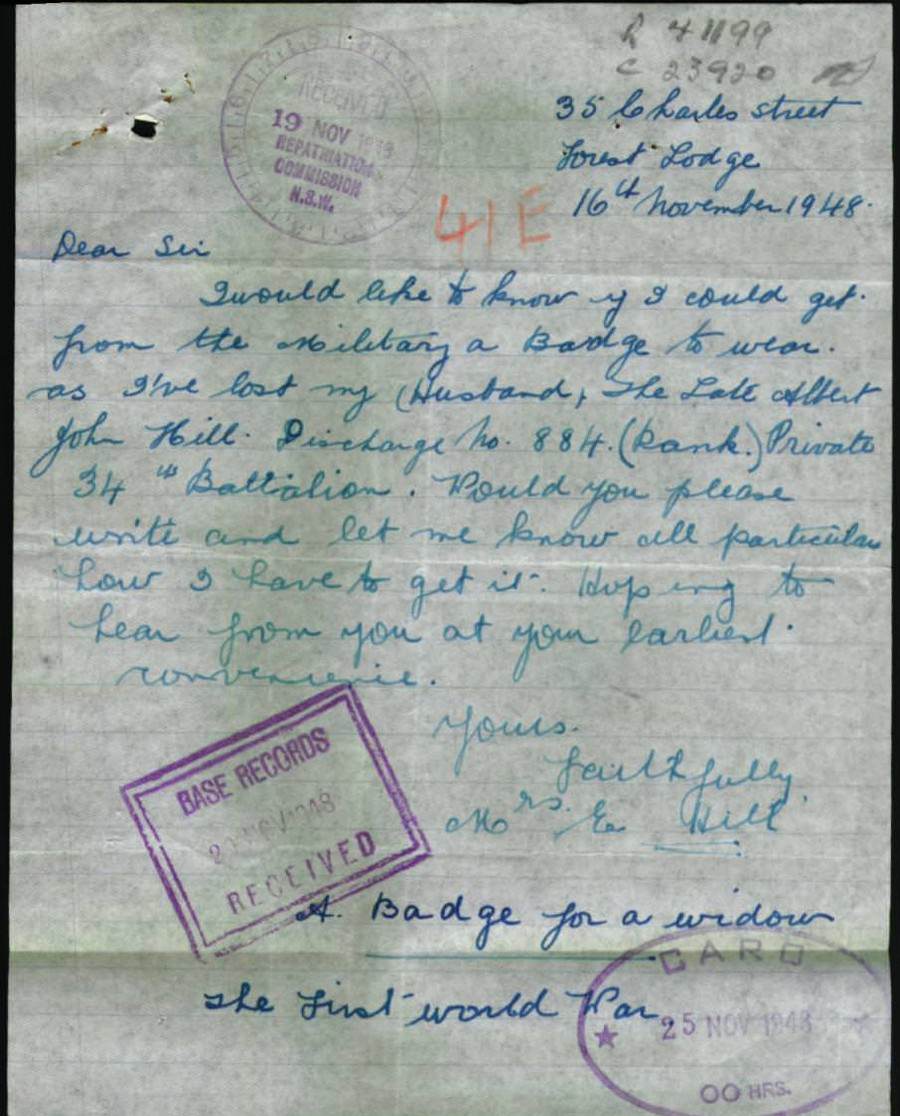

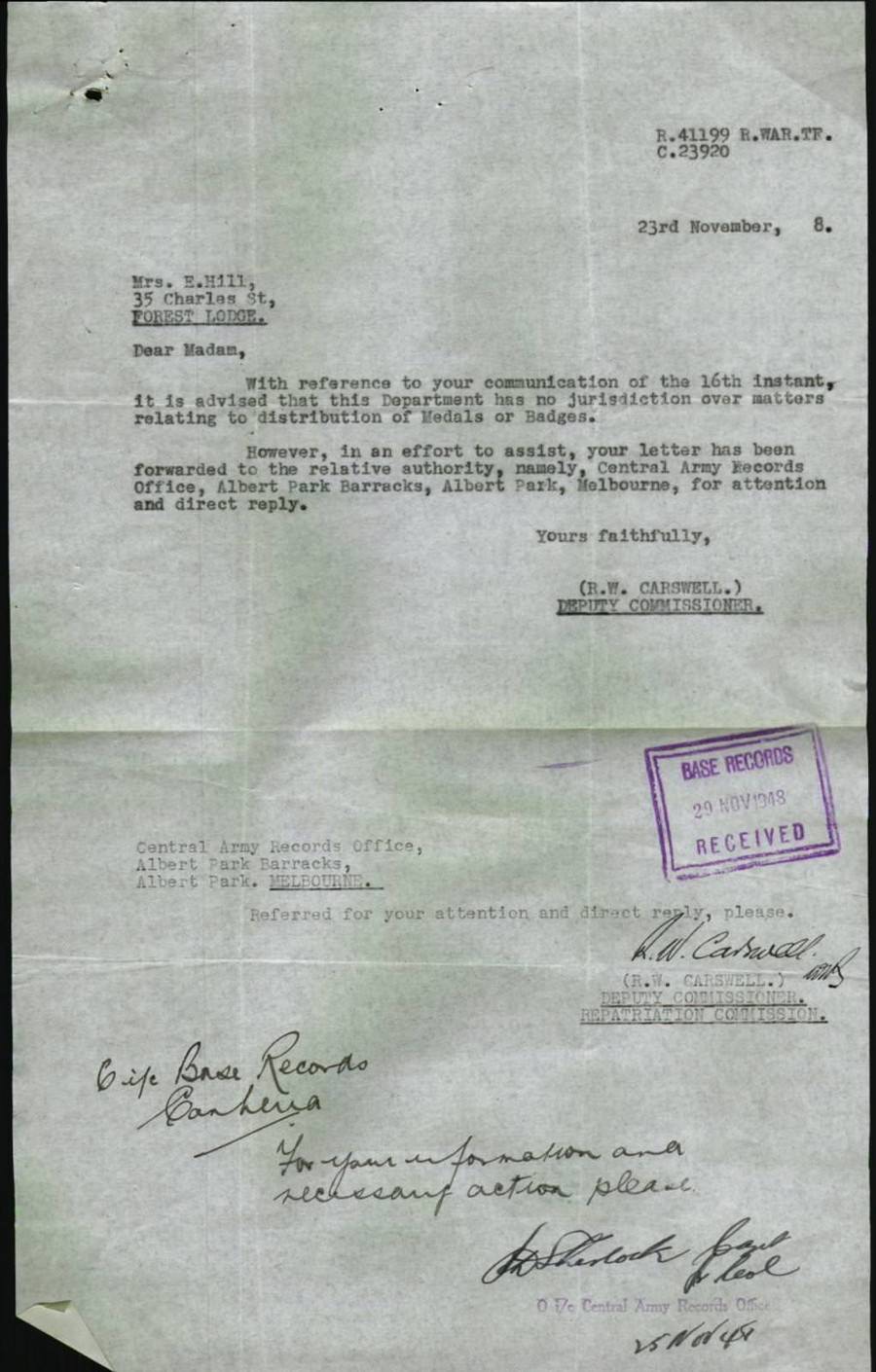

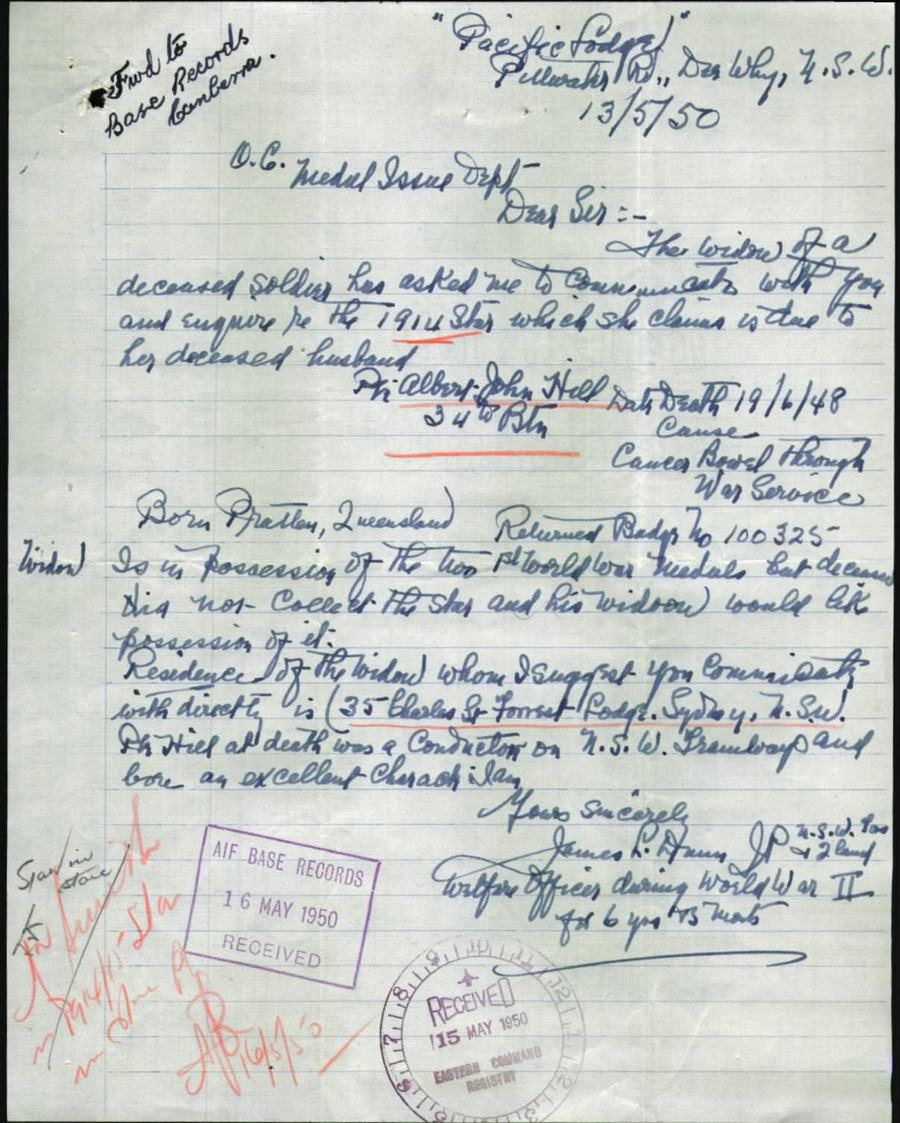

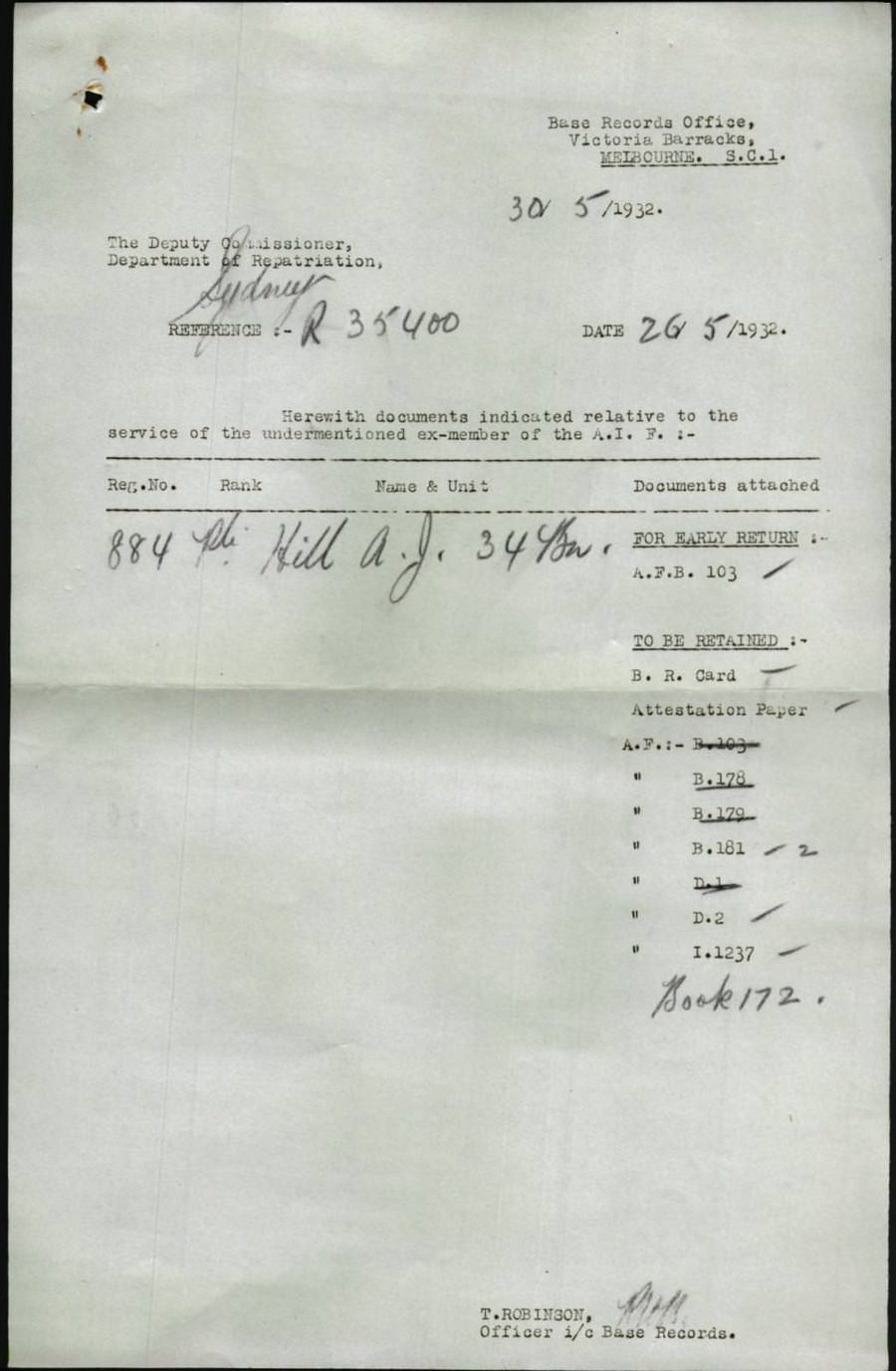

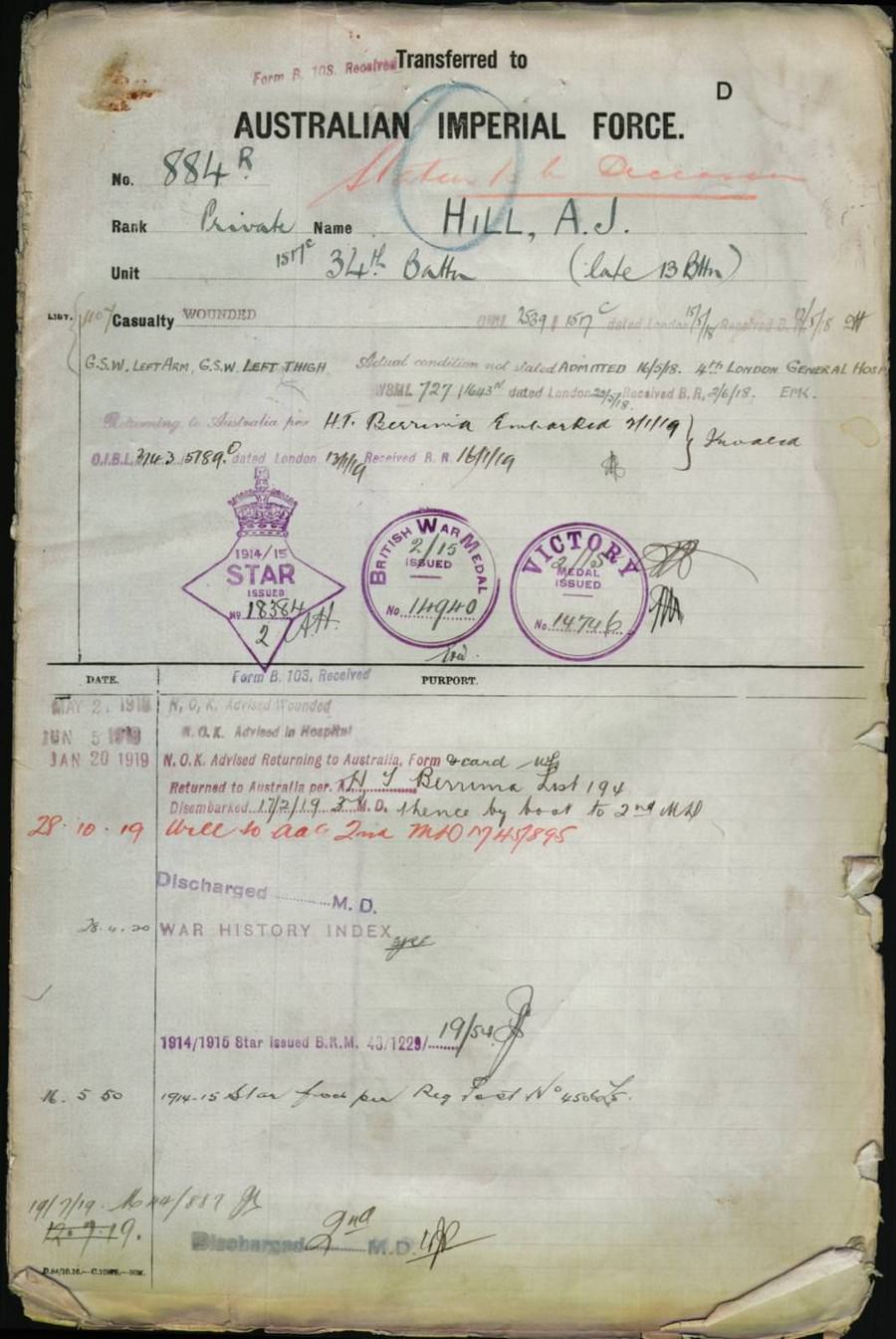

Military Records

(Australian National Archives)

(Australian National Archives)

Under Construction; 21/03/2015 - 05/11/2020.