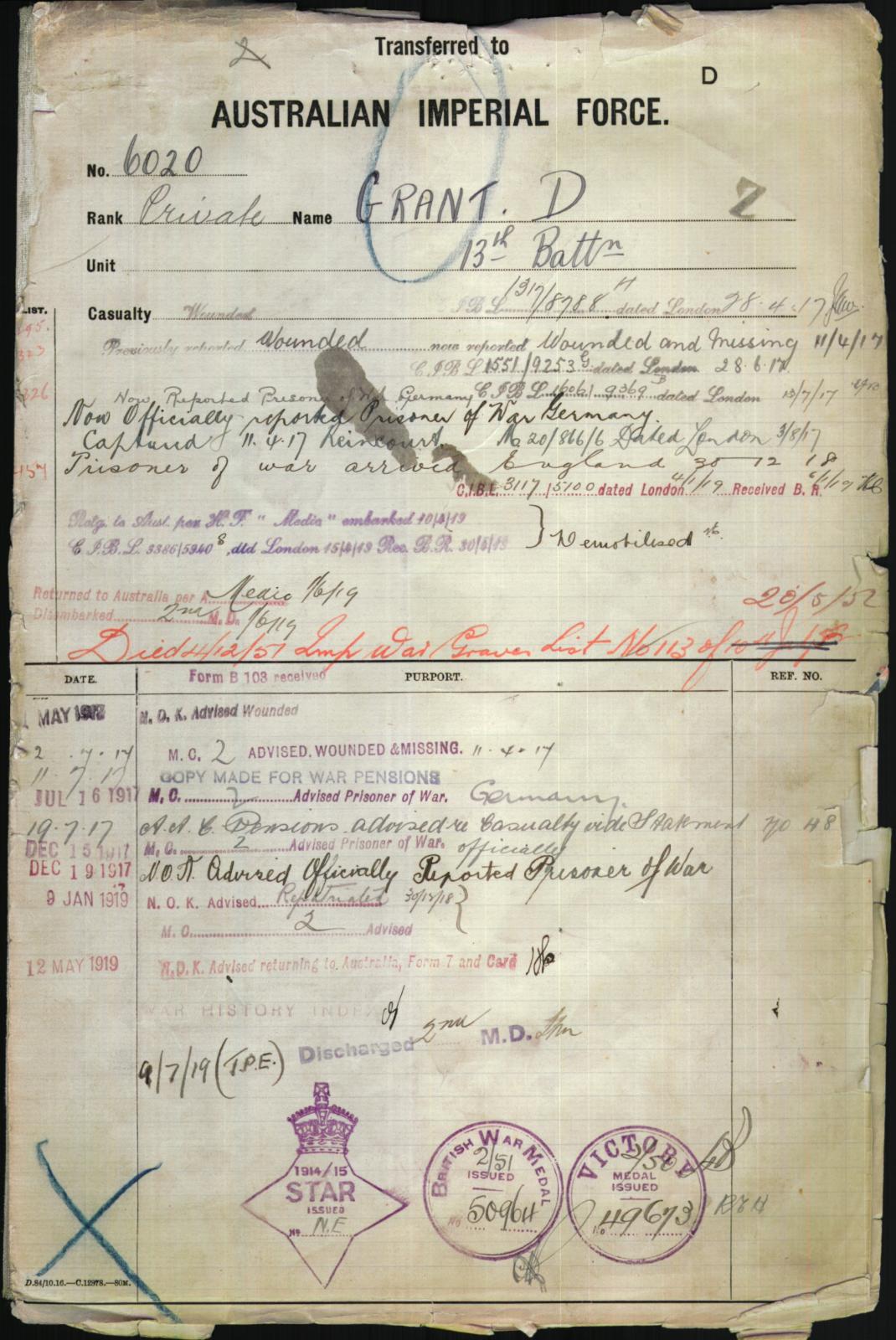

The Argus, Saturday 19 September 1925

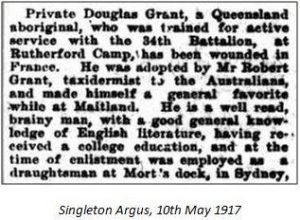

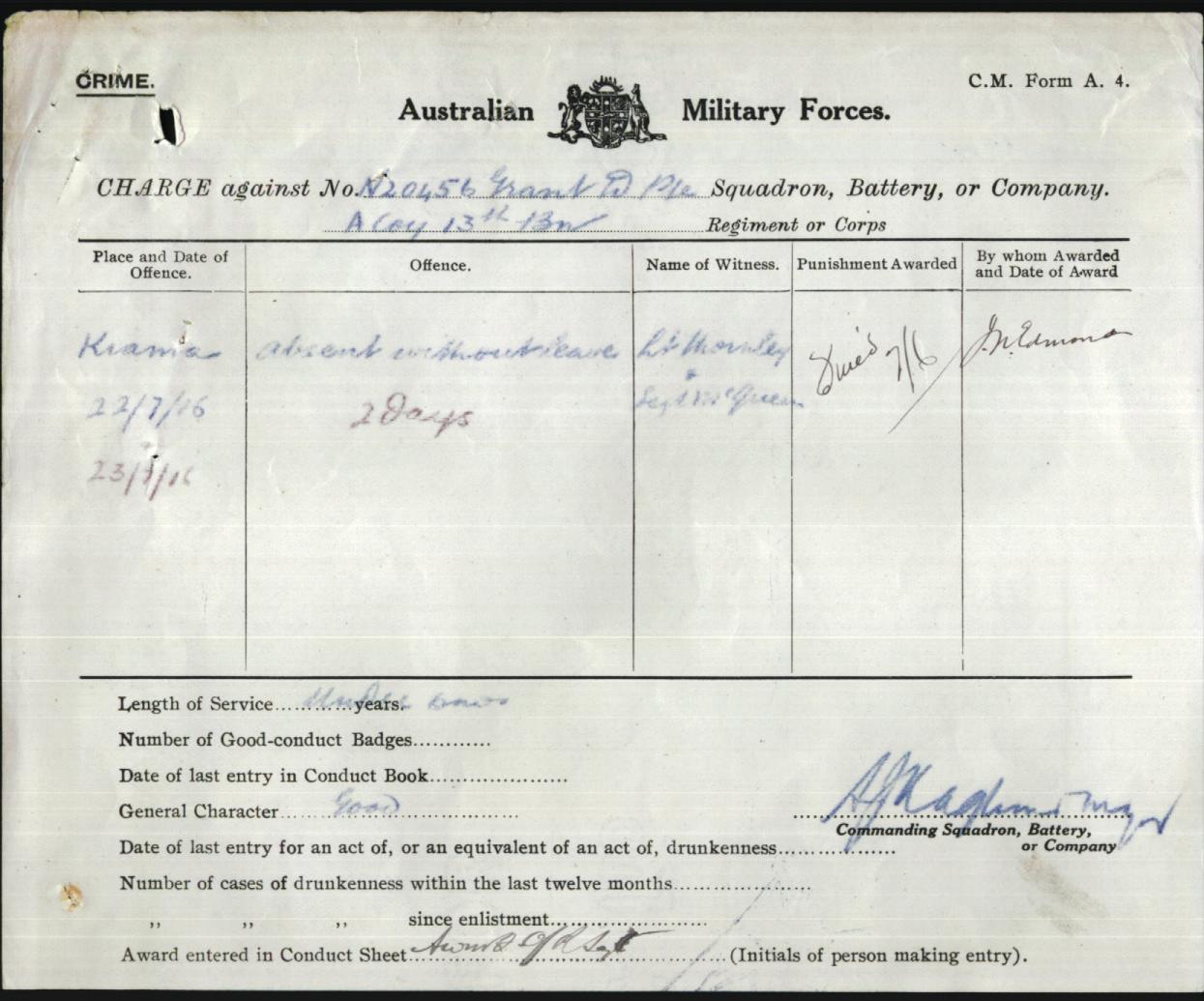

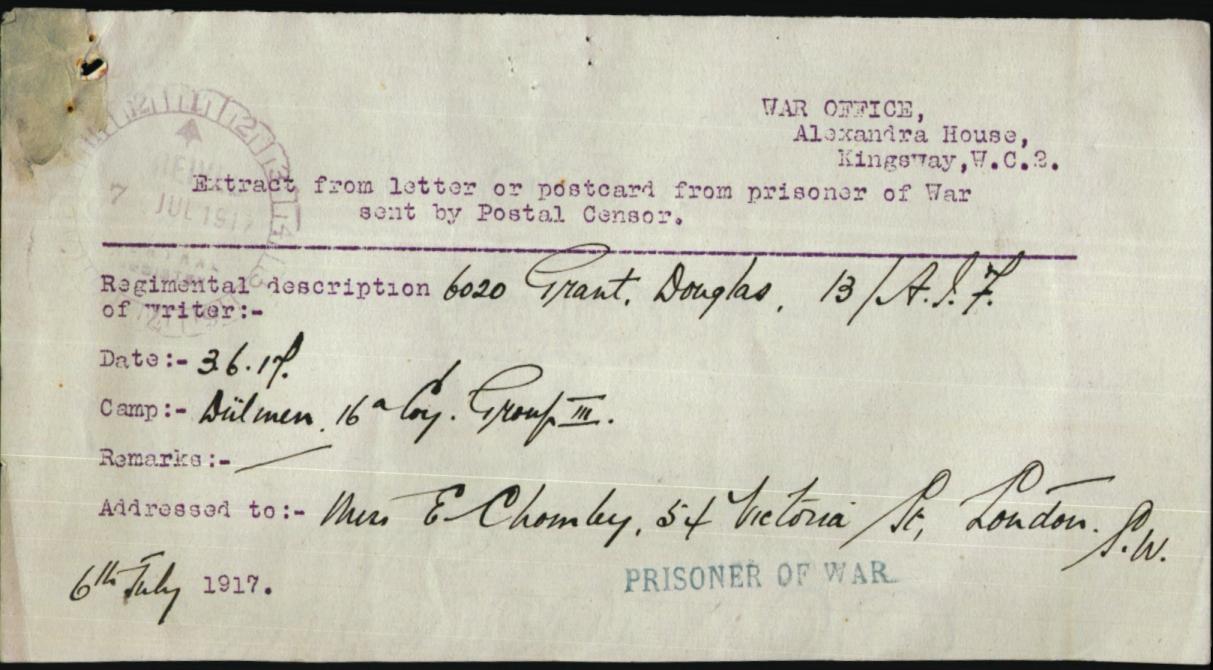

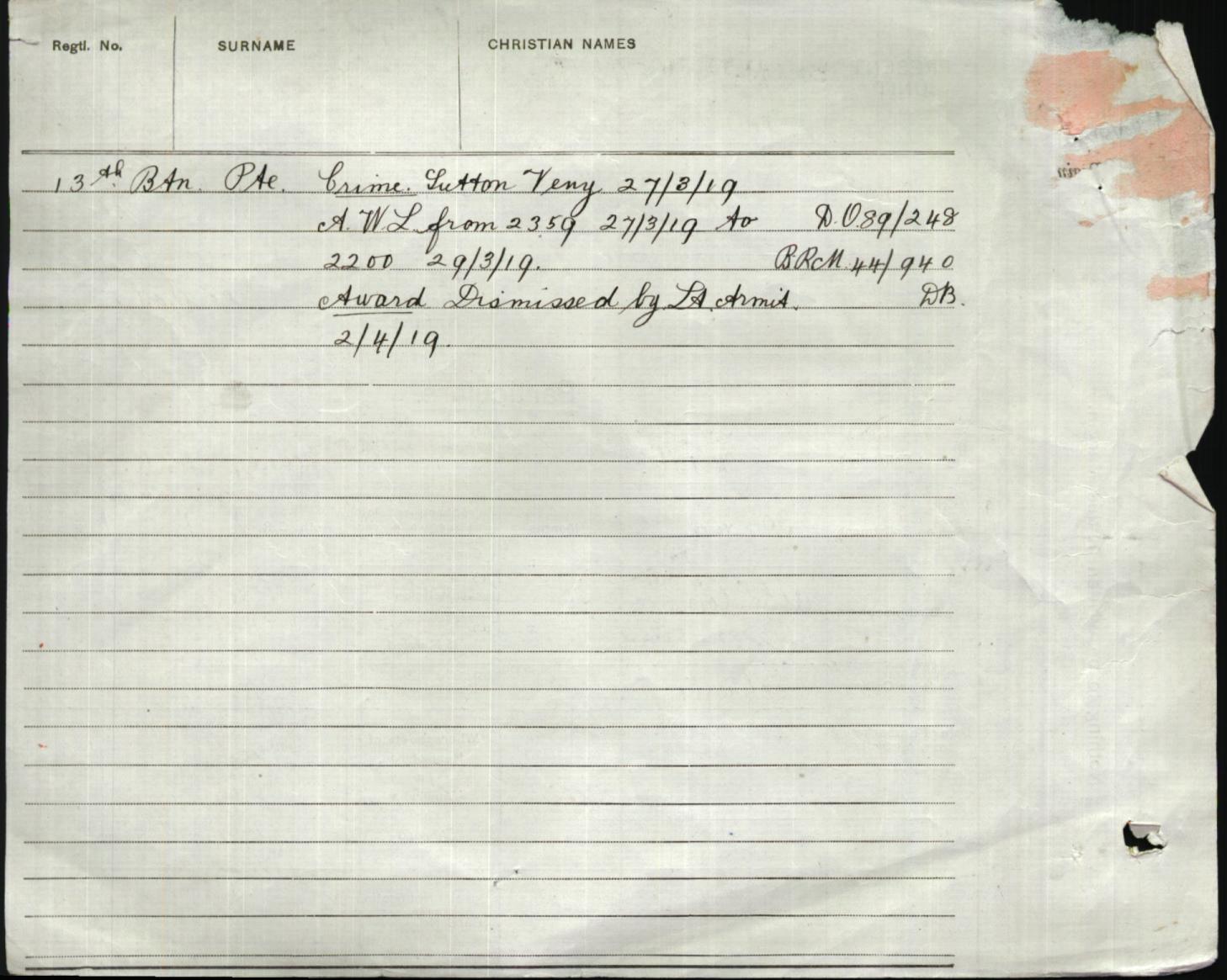

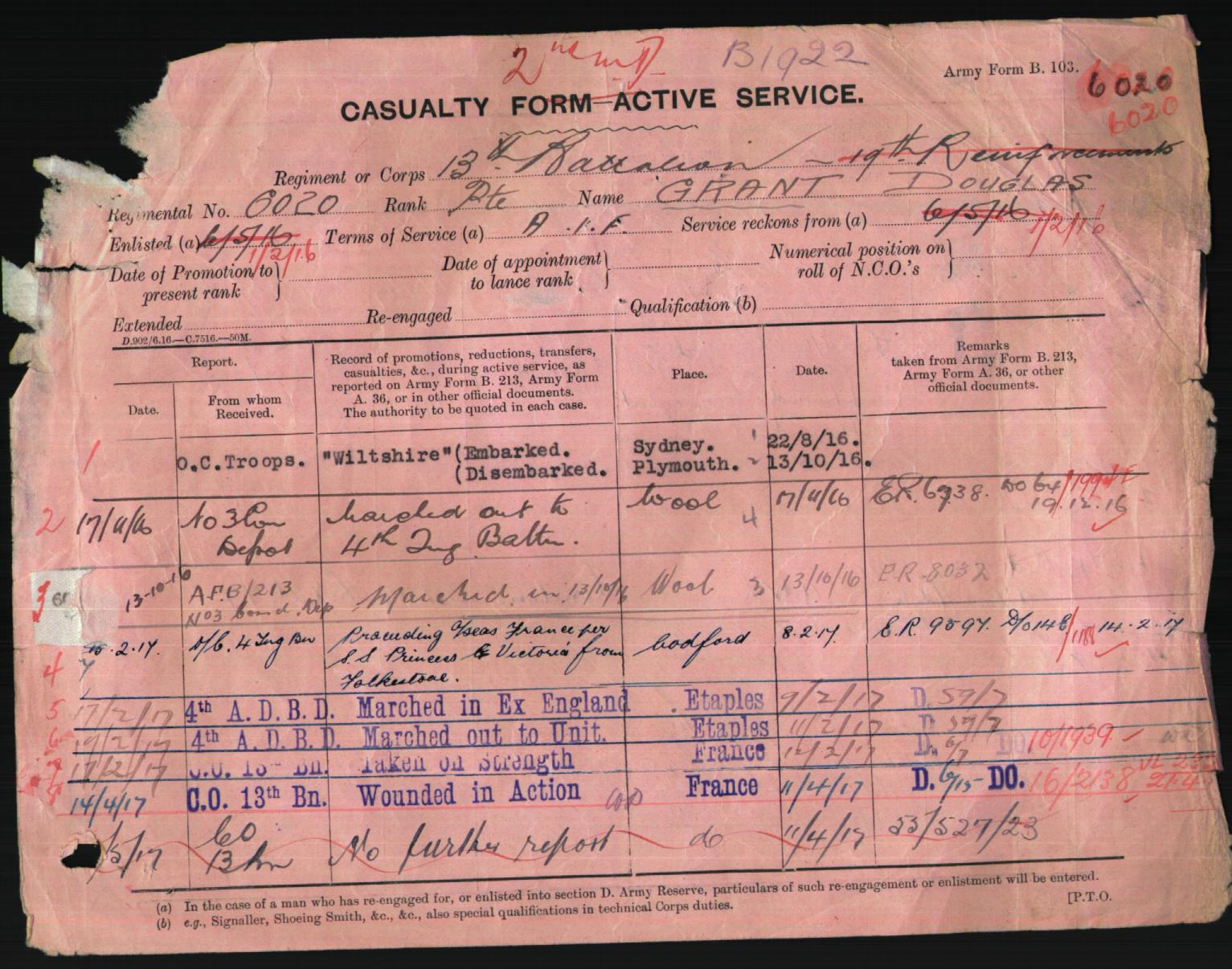

ABORIGINE ASSAULTS CHINESE. “A Misapprehension.” Allegations that he had been assaulted in Little Bourke street by Douglas Grant, aged 40 years, an aborigine, were made at the City Court on Friday by Jimmy Goon, cook, an aged Chinese. The bench consisted of Mr. R. Knight, P.M., and Messrs. T. O’Callaghan… Grant was charged with having unlawfully assaulted Goon on September 17. Goon said: – About 5 o’clock on Thursday afternoon I was walking along Little Bourke street. Grant called me an offensive name and then hit me on the eye. Constable Tankard said: – When I spoke to Grant he said that he did not remember whether he had assaulted Goon. Grant was under the influence of liquor. Grant said: – I am not an antagonistic man. I was born in Queensland, and I was a prisoner of war in Germany for two years. I am suffering from war disabilities. I am very sorry if I assaulted this man, but I think it is a misapprehension. Mr. Knight. – You should not drink. Grant. – They all say that. (Laughter.) Mr. Knight. – You had better keep out of hotels. They have no right to serve you. If you had not been drunk you would not have hit that old Chinese. In the circumstances you will be fined 5/, in default imprisonment for six hours.

Geraldton Guardian, Tuesday 13 October 1925

GOOD SAMARITAN’S LUCK. Jimmy Goon, a Chinese, of 80 years of age, who resides in Little Bourke St, Melbourne, was, the other night, walking along that delectable thoroughfare when he saw an aboriginal stretched full length in the gutter. Bending over him, Goon said, “No good you stop here, velly much cold,” and sought to raise the fallen brother. The latter came to life very suddenly and smote the good Samaritan on the nose with such violence as to cause him to see a multitude of stars…

The Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 18 April 1931

A TRAGIC STORY. Slaughter of Blacks. Without doubt, the darkest page of Australia’s history relates to the cruel and ruthless attitude of the early settlers to the aborigines, who were driven from their hunting grounds, slaughtered and deliberately demoralised until, as we know, many tribes were exterminated… The rapid occupation of territory as the settlers pushed farther and farther back from Sydney deprived the aboriginal of his means of subsistence, and, whether he fought or accepted the situation, the result was the same. If he attacked the whites or preyed upon their flocks and herds he was shot down, and if he made friends with the newcomers his destruction came just as inevitably, for he was only too ready to copy the vices of the station hands and the disreputable characters who resorted to their camps.

A CHIEF’S APPEAL. Following a demand that a punitive expedition should be sent against a particular tribe suspected of having committed murder, the explorer Eyre wrote: “If Europeans placed under the same circumstances were equally wronged and equally shut out from redress they would not exhibit half the moderation and forbearance that these poor, untutored children of impulse have invariably shown.” Nevertheless, the expedition was organised, and “succeeded” in practically wiping out the whole tribe…

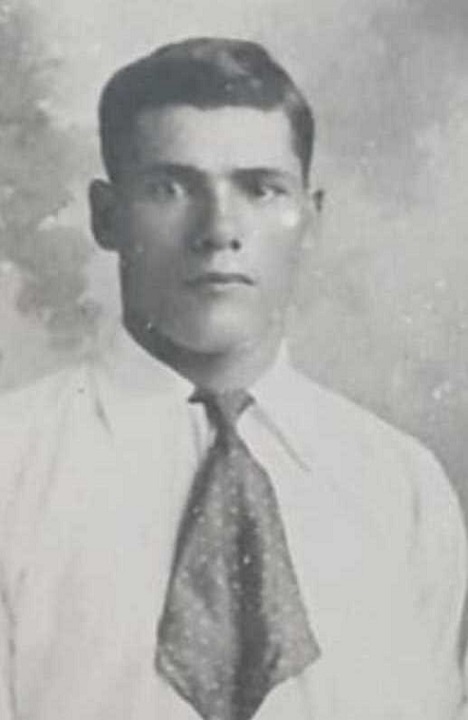

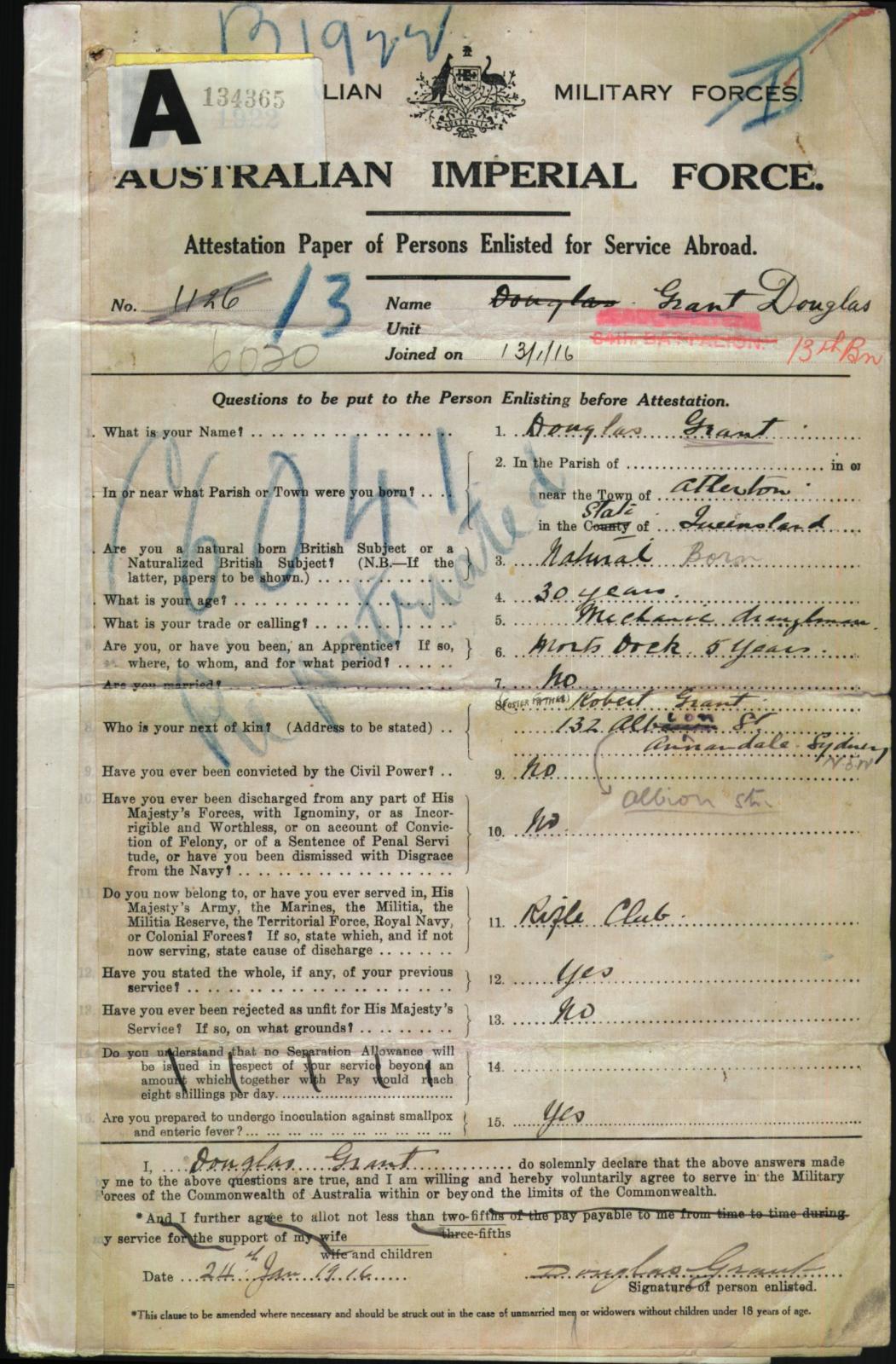

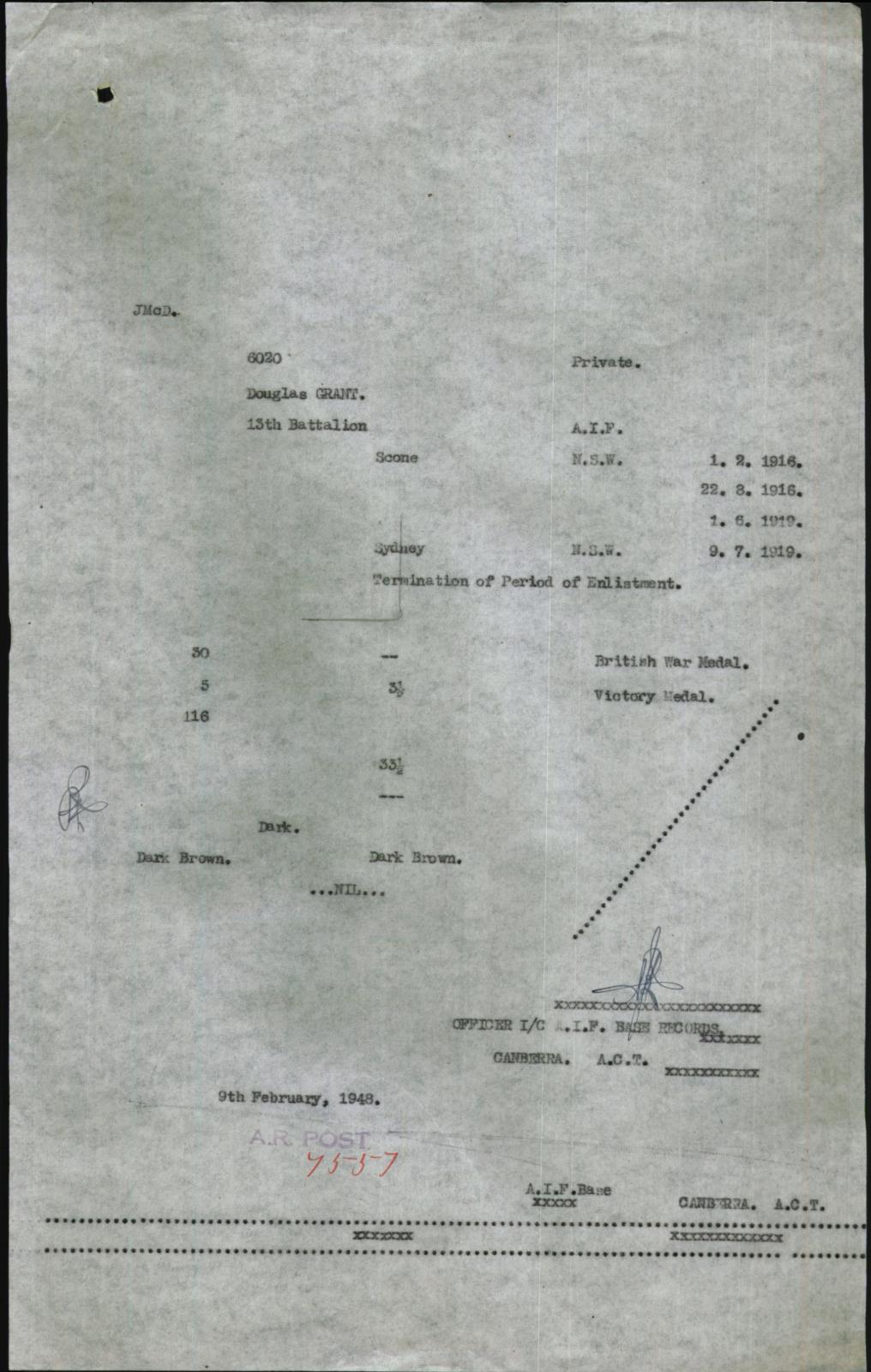

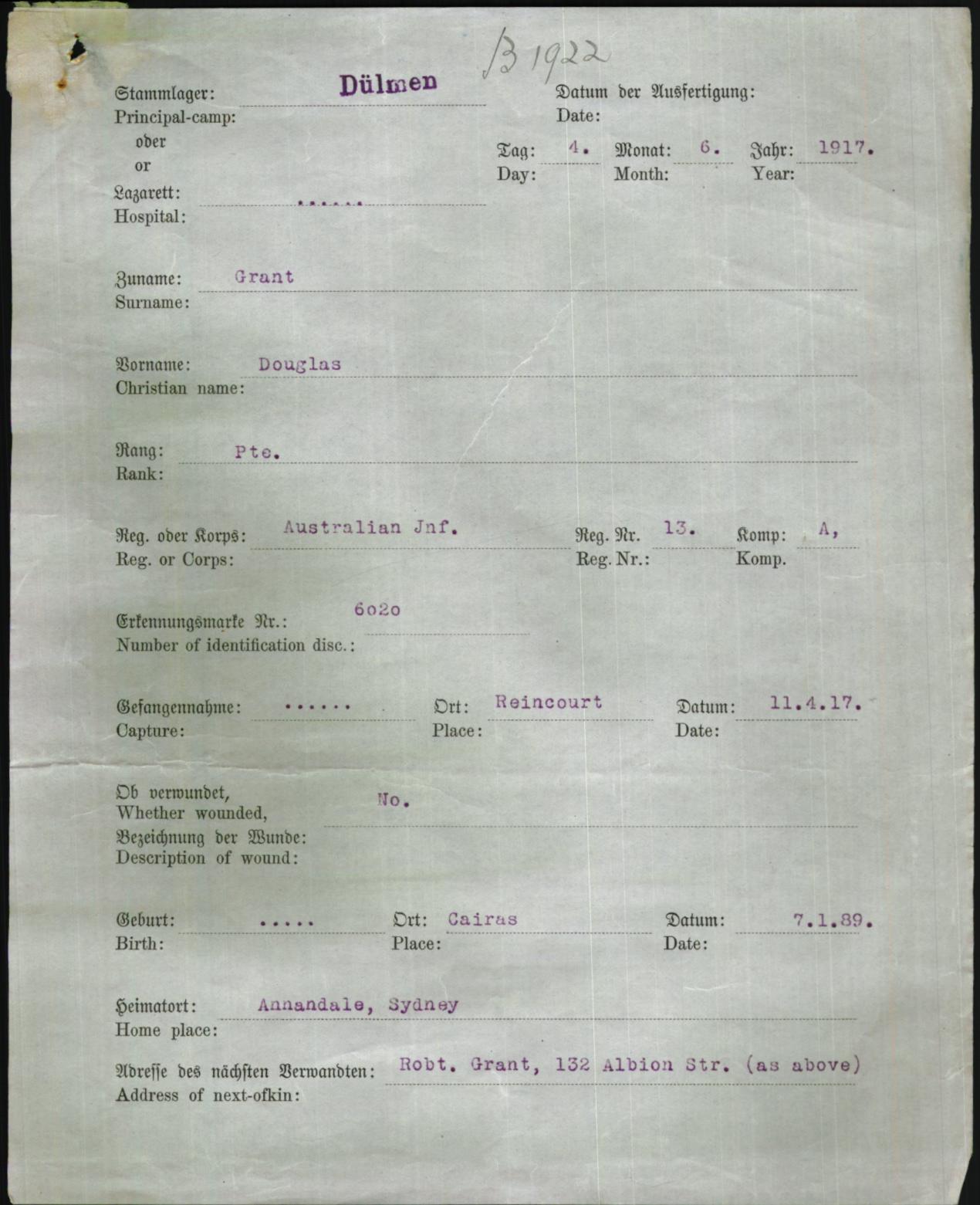

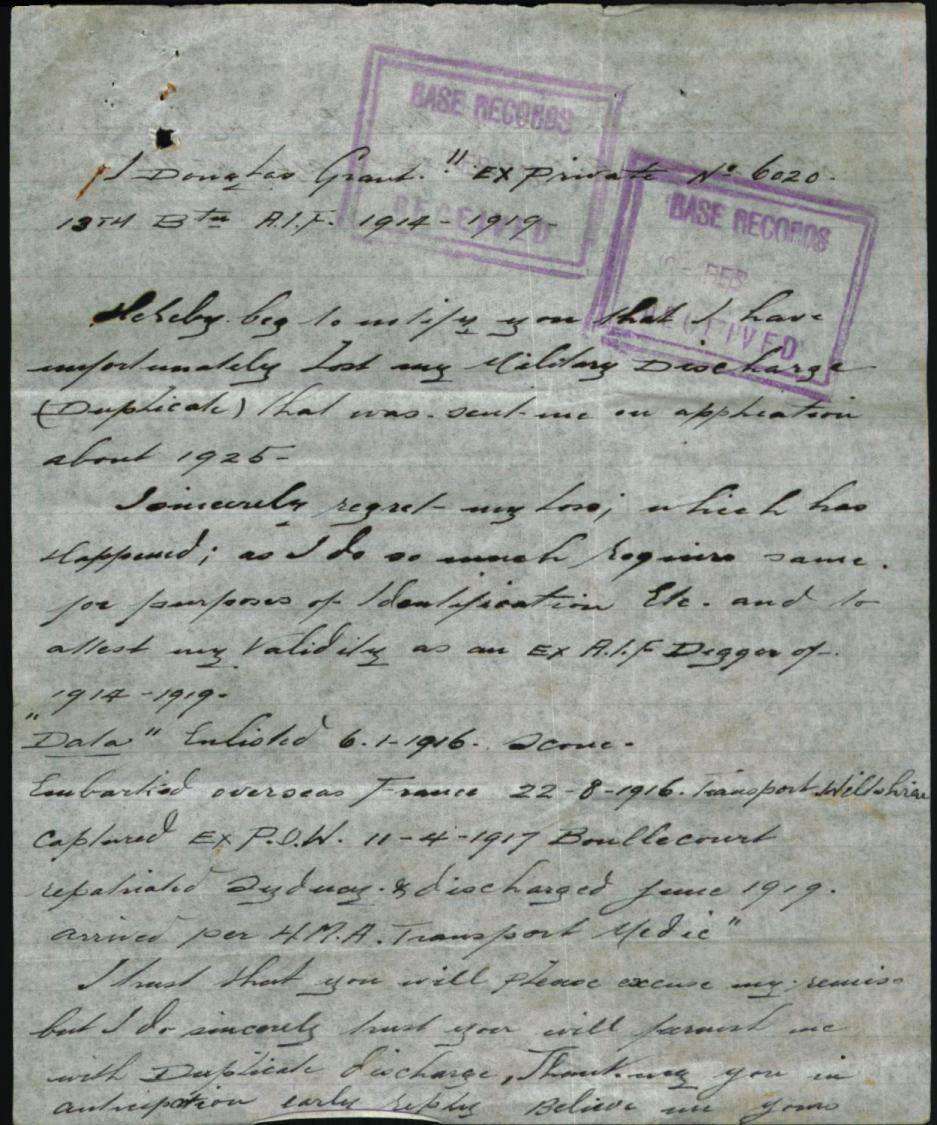

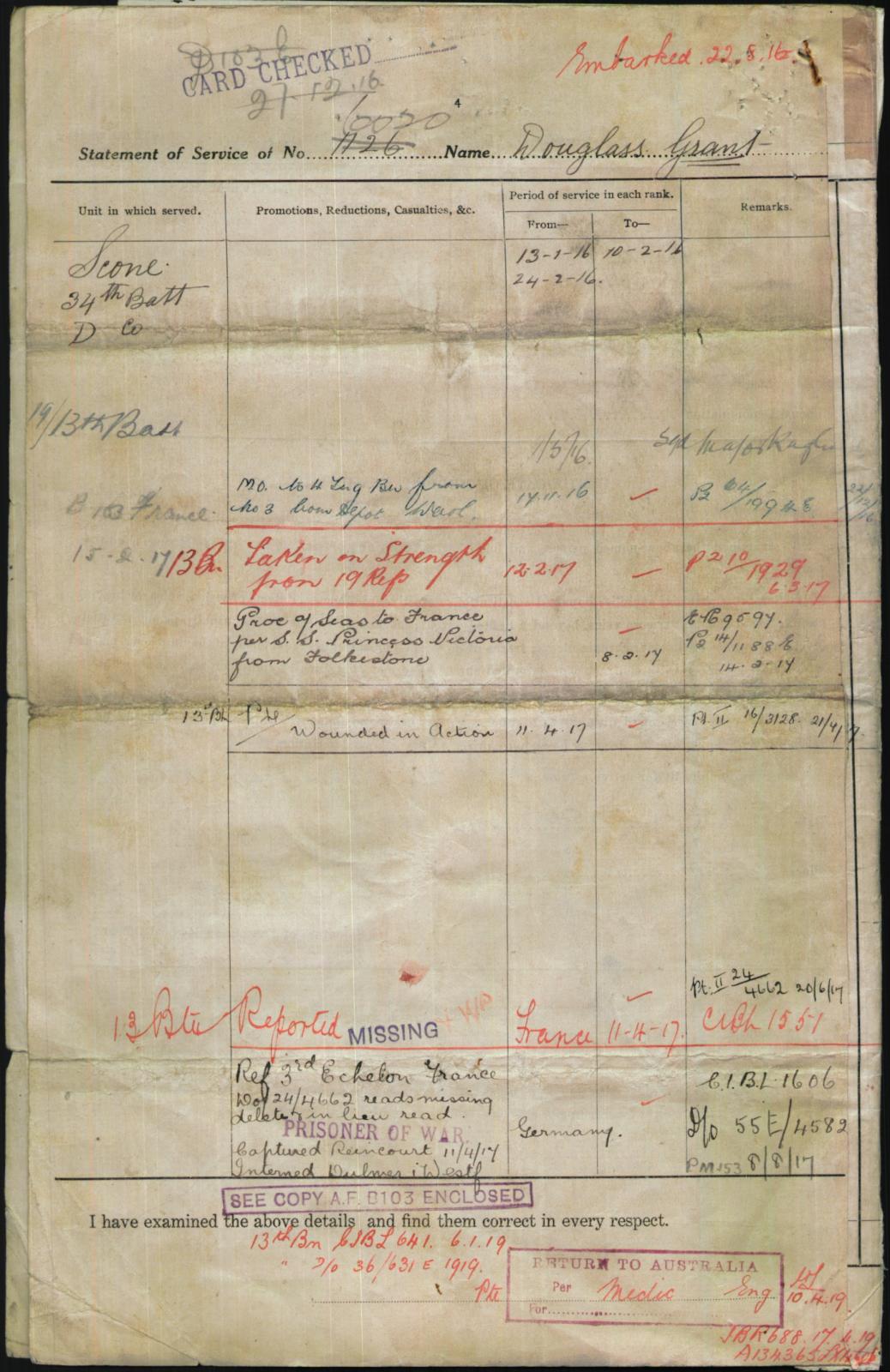

HIGH INTELLIGENCE. No person who has ever come into touch with the unspoiled full-blooded native will agree with the popular notion that the Australian aboriginal is of inferior intelligence. His tribal system had many fine characteristics, and his moral and social laws were strict and in some cases, exemplary. A few members of the race have even triumphed, in the sphere of our so-called modern civilisation. Douglas Grant, for example, who was adopted by Mr. Grant, of the Australian Museum, was for some time one of the most efficient wool classers at Belltress, Scone. Selecting for his profession that of draughtsmanship he was employed in one of the biggest engineering shops in Sydney — Mort’s Dock. He is a Shakespearean student, and served with distinction in the A.I.F., in which he attained the rank of sergeant… These cases suggest that in the neglect of the black population in the past there has been a wicked waste of human material in Australia, and that had the original tribes been encouraged to adopt the ways of the white man and been given a fair and sympathetic opportunity to make themselves useful citizens they would have been an asset to the country, which, after all, was their birth-right.

The Sydney Morning Herald, Saturday 1 August 1931

LAWSON AND MUSIC. A Shearer Violinist. (BY KEITH KENNEDY.) It is not usual to associate Henry Lawson with the musical art, his works being more reminiscent of the cracking of stockwhips, and the creak of the mining windlass. Having Gipsy blood in his veins, however, it is not surprising to find that he was profoundly affected by melody and harmony… I have the good fortune to be possessed of a violin that formerly belonged to one of Lawson’s mates. On the back of it is inscribed, “To my mate, Perce Cowan and his violin, with gratitude for light in dark hours-Henry Lawson.” Cowan was a shearer, and, many years ago, he and Lawson were often together “on the wallaby.” When the war broke out, Cowan enlisted, and went to the front.

After the Armistice he returned, and, in Sydney, renewed his friendship with Lawson. Another returned soldier who was a close friend of both Lawson and Cowan is Douglas Grant, a highly educated Queensland aborigine. Douglas is the only one of the three now living. On being shown the violin he greeted it as an old friend, and told how he and Cowan, with the violin, used to go over to where Lawson lived in North Sydney, when Cowan would play, while Lawson sat at the table and wrote. With tears in his eyes, Douglas vividly described the little room, even going into such details as an old newspaper being spread on the table in lieu of a cloth.

The Don Dorrigo Gazette and Guy Fawkes Advocate, Friday 4 September 1931

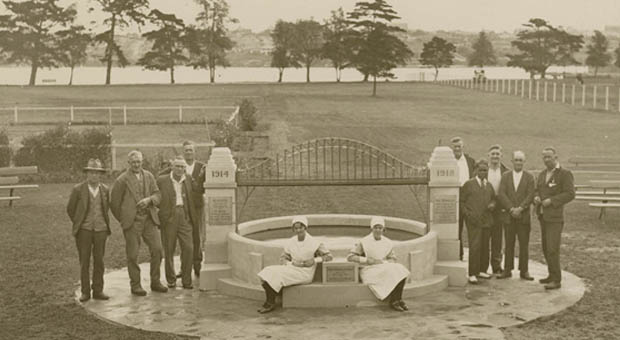

The constructive fancies of the aboriginal Douglas Grant are not limited to the decorative pool and bridge just admired by the Governer at Callan Park, says a city journalist. This dusky hero of the A.I.F. tried last year for the job of designing the new houses for the La Perouse abo. settlement. And just before that, he humped a hundred-weight of solid sandstone from the Avon Dam to the Sydney Museum in the hope (alas, blasted) that an impression in the rock was a human footprint from the dim Triassic era. It is 40 years since the sturdy Scot, Robert Grant, picked up a black waif, while travelling for the Australian Museum in North Queensland. That waif is now the well-educated Douglas Grant. However, it seems that Grant has had a mental break-down, and is now on the shelf for a while.

Northern Standard (Darwin),Tuesday 15 September 1931

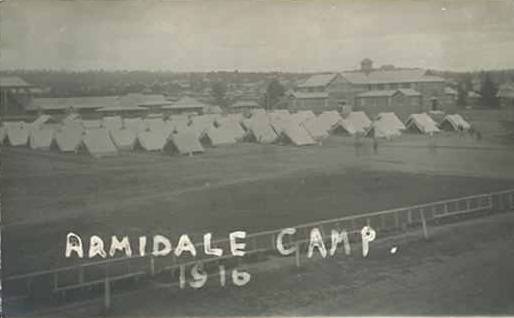

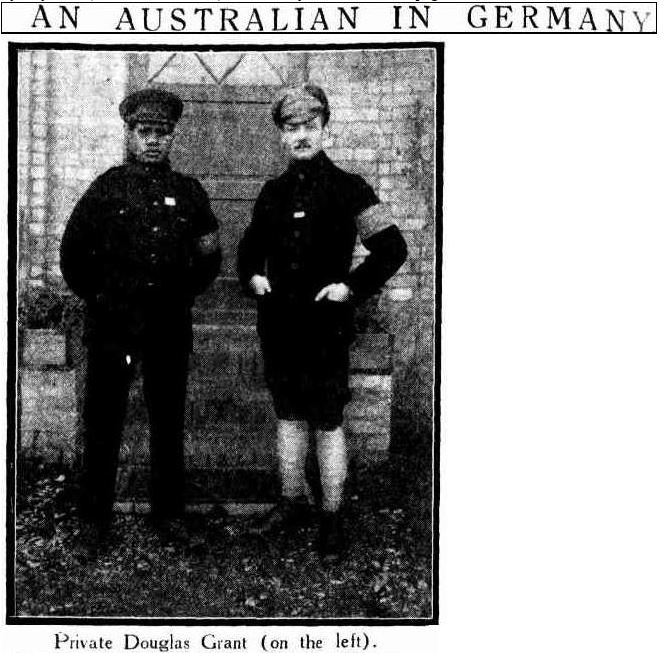

ABOS. WHA’ HAE There is a neat note of humor about the full-blooded abo., Douglas Grant, whose Harbor Bridge model and concrete fish-pond have just been opened by the Governor at Callan Park. Inheriting from his sturdy foster-parents a rich Highland brogue, he has staggered many a Scot visiting Sydney with the greeting: “Hoot, mon, hoo are ye the noo?” Before leaving for the world war with the 13th Battalion – the only full abo. in that scrap – he jested with a few cronies about a blackfellow fighting for a White Australia. He whimsically added that Kitchener would doubtless say to him: “What the devil are you doing with the A.I.F.? Get off to the Black Watch!”

nurses Arrow, Friday 23 October 1931

Nurse Edna said she will always remember her first day at Callan Park…”One patient, who was suffering from a bad attack of nerves, but who is now well enough to leave any time he chooses, is the noted soldier and architect, aborigine Douglas Grant. He designed our War Memorial, a clever replica of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, spanning a large gold-fish pond, which Sir Philip Game opened in June… “Some of the patients imagine they are public figures. We have two who think they are Mr. Lang, and they delight in issuing orders to everyone. We keep them apart, in case they should try to fight out their right to call them-selves the Premier.”

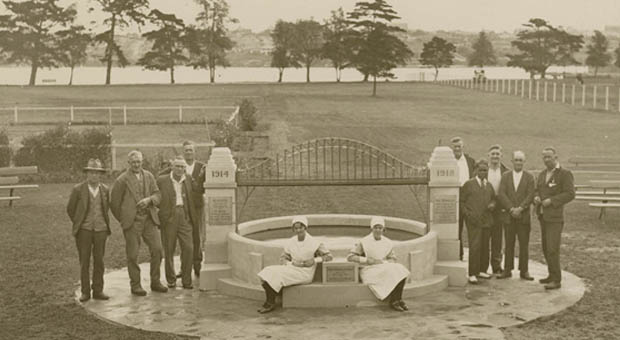

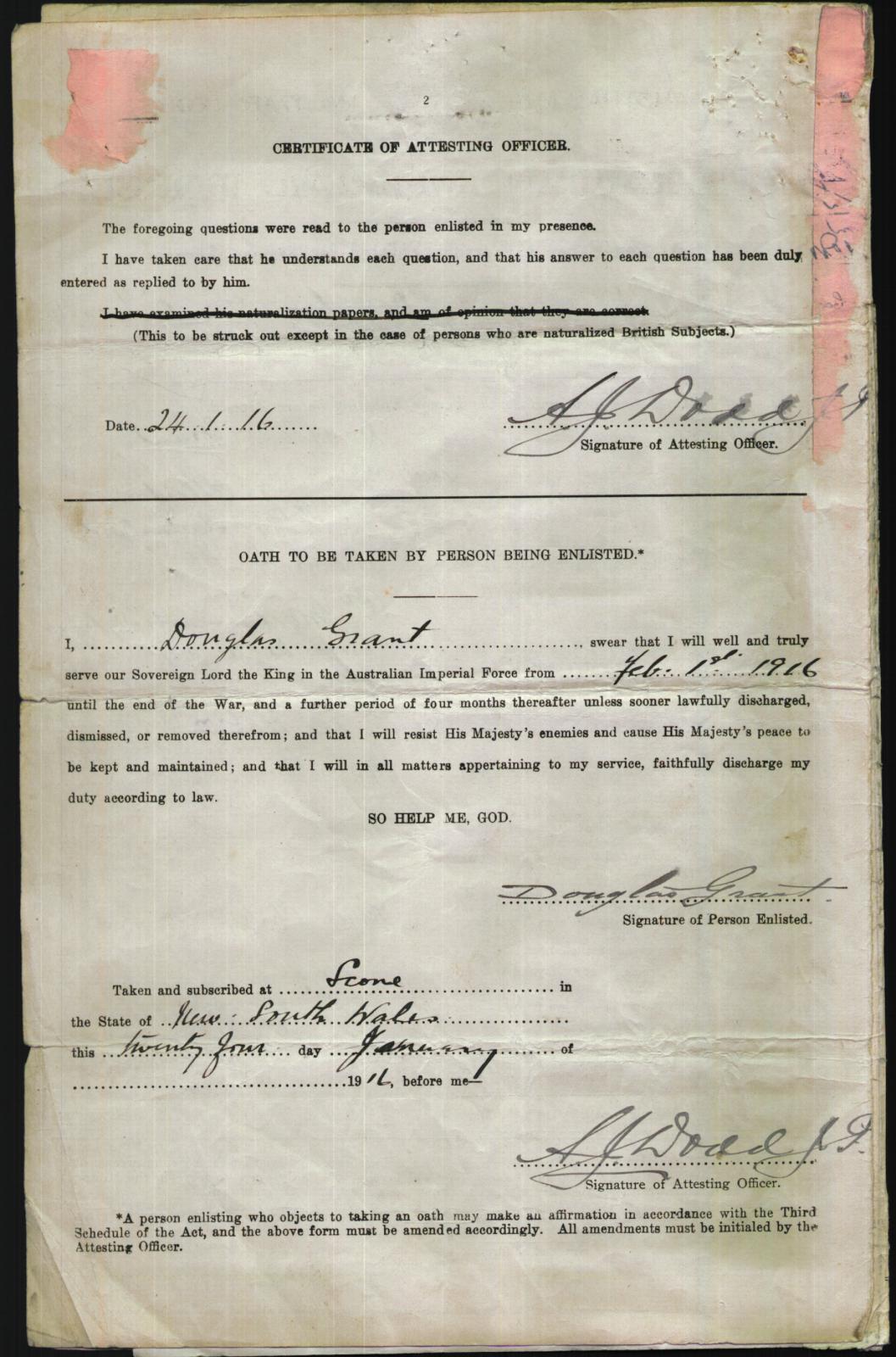

Douglas Grant, nurses and ex-servicemen gather around the war memorial built by Grant at Callan Park, which featured an ornamental pond and a replica of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, 1931

Scale model of Sydney Harbour Bridge above a circular wishing well. Bridge pylons made of sandstone and the well is made of concrete.

The memorial is outside a building on Military Drive within the old Rozelle hospital grounds. The memorial faces the southern corner of Callan Park Oval.

This memorial was unveiled by His Excellency Air Vice-Marshal Sir Philip W. Game G.B.E., K.C.B., D.S.O. Governor. 4th August, 1931. Donated by Sydney Legacy Club

(Photograph courtesy State Library of NSW, Digital Order number a368022)

Townsville Daily Bulletin, Thursday 2 February 1933

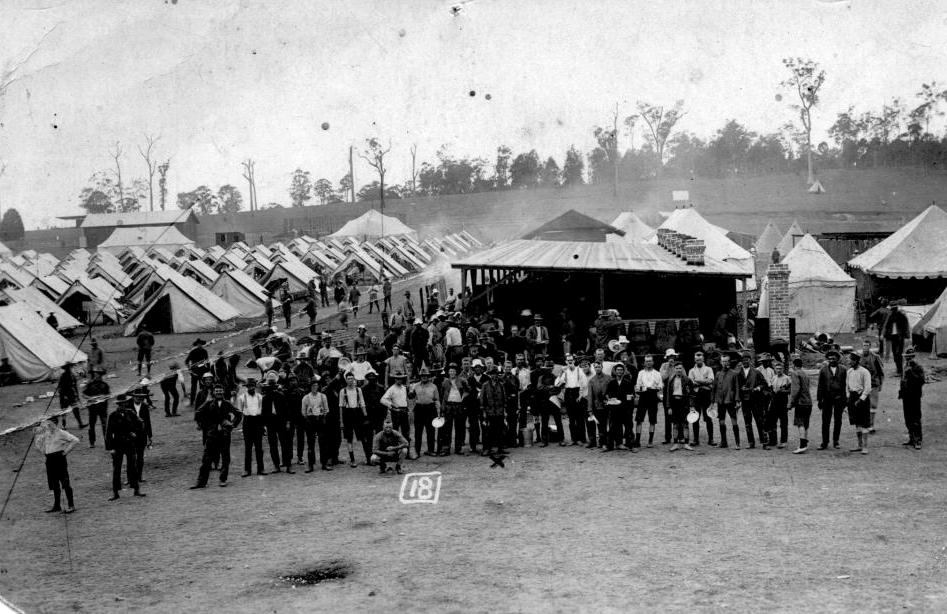

DOUGLAS GRANT. Queensland Aboriginal A.I.F. Digger. (By Fred. G. Brown). Now for the true history of Douglas Grant I know, because, as I have already said it was I who saved his life. I am not sure of the year, but it was in the early nineties. One day just before the mid-day meal hour, Willie Joss… and I were having lunch when I saw running down the track towards the hut a miner whom I knew at once was George Goodson. I said to Joss “What’s the matter with Goodson — his clothes are nearly torn off his back?” Before he could answer, George rushed into the hut saying “The niggers have killed Frank.” This referred to Frank Paaske, a Swede, who was George’s mate…

Next day the Sergeant, the two black trackers and myself, started out on a nigger hunt… I swore to myself, if I got an opportunity I would shoot to kill: this decision was enhanced by conjuring up at various times in my mind’s eye the mutiliations on the murdered man’s body… My weapon was an old Schneider rifle — what a terrible weapon it was. Makes a bigger hole leaving a body than on entering it… As a nigger came straight towards me, I fired and as he immediately turned and ran, I said to myself “Good God! I’ve missed him.”… The bullet had entered his chest and making a big jagged hole, came out through his back. How he ran the few yards he did was a mystery. In a few minutes quietness reigned and we all collected and found our live number had increased by two gins, who had been captured by the trackers and a boy of about five or six years of age.

The little abo we had captured seemed to know that I was protecting him. Sucking his thumb he edged towards me and away from the others, eventually getting right alongside of me, and in fact scarcely left my side during the next two or three days that we roamed the scrub. The problem of what I was going to do with him was solved by Jack McCrohan in this manner. He said, “There are a couple of taxidermists camped up in the Pocket collecting specimens of natural history (for the Rothchilds Museum at Tring, I believe). One named Grant is married. The other, I believe, named Cairns was not married. Mrs. Grant was down here the other day and remarked she would like to get a little black boy.” In leaving him with her I knew that he would be well-looked after. She looked a motherly soul.

Next day I left for the Russell Goldfleld and have never seen Douglas Grant since, though I heard that the Grants had adopted and given him a good education… As can be expected the aboriginals kept away from the Field for some time after they had been “dispersed”… They gradually came back again and in a short while became quite friendly with the miners and worked with them for years during which time there was never any further trouble and they were treated with every consideration. Perhaps the method of dealing with them may be considered by those who know nothing of the trials of the pioneer somewhat drastic, still it was a matter of “white” or “black” ruling… However, that is the true story of Douglas Grant.

Glen Innes Examiner, Thursday 2 March 1933

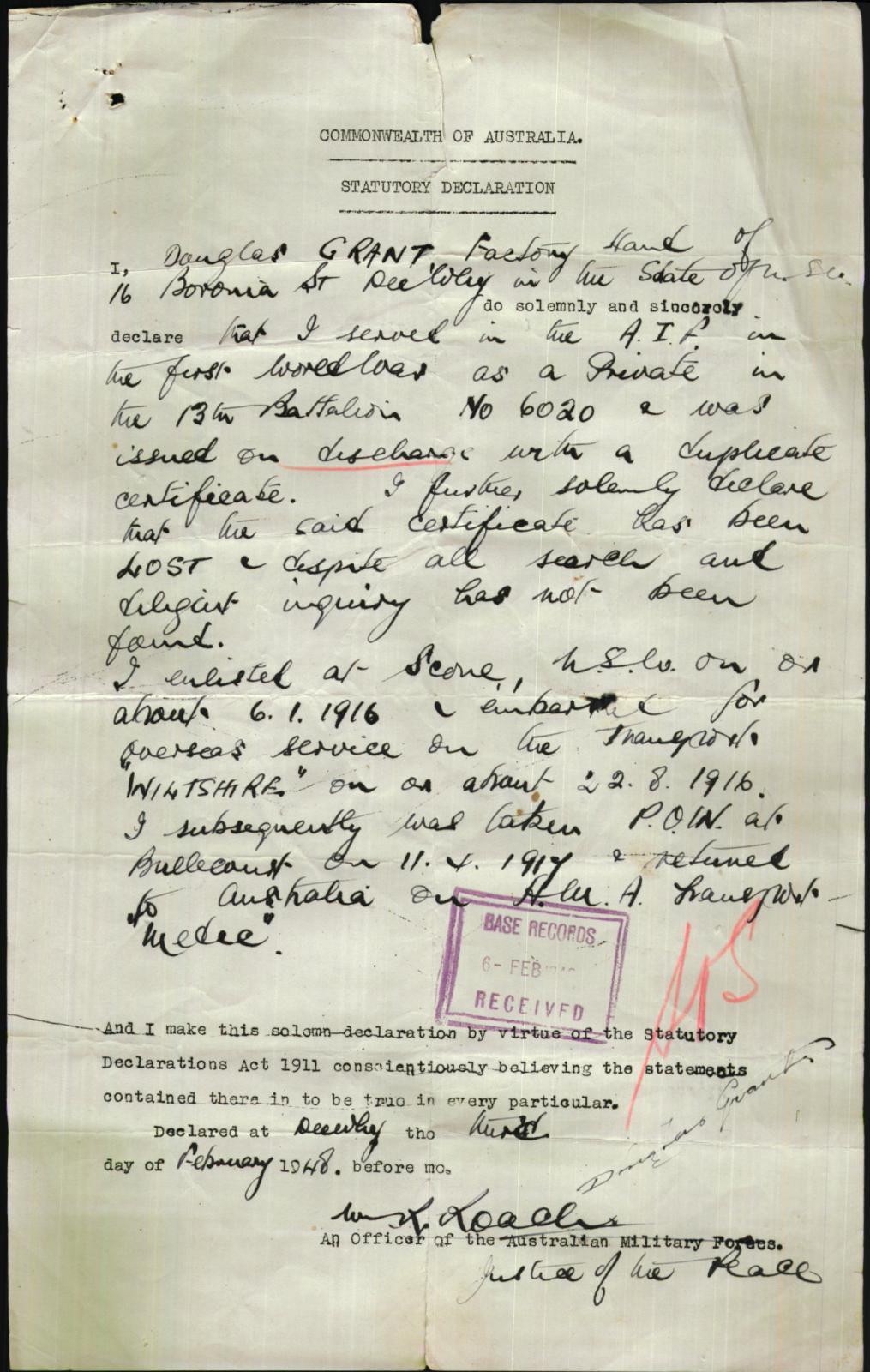

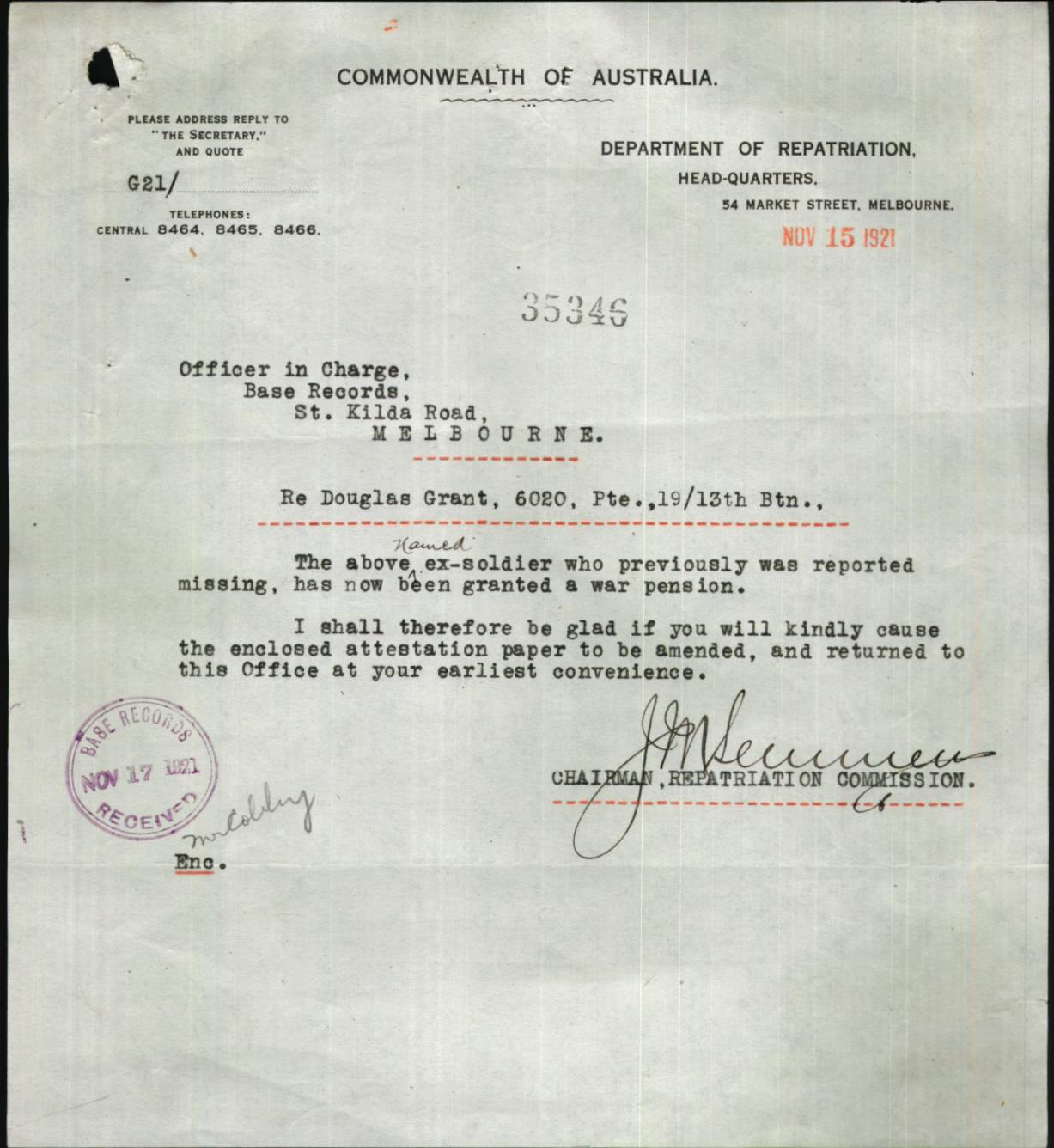

OWN TERRITORY Plea for Aborigines Back to Communal Life Pleas to allow the aborigines to have their own colleges and schools as had the Red Indians of America, was made by Douglas Grant, a Queensland aborigine, in a talk to the questions circle of the Balmain Methodist Church. Mr. Grant, who was adopted when he was only 18 months old, and educated to a standard fitting for a position as draftsman in the Sydney dock yard, served with the Australian Imperial Forces, and was a prisoner of war in Germany for 22 months. If the aborigine to-day, he claimed, were given the opportunity to develop free from white influences the high communal spirit of pre-settlement days, he could be used usefully to occupy the outposts of the continent, where at present the European could not go, he said. Let him develop naturally, not merely stay around the mission. Let him become an asset not a drag. Although the Australian native was put down as one of the lowest types of the human race, Mr. Grant said that his communal life was of a far higher standard morally than was much of the European life to day. Even to-day tribes were to be found living the same primitive life which the natives had lived from time immemorial. Instead of fostering this spirit he said, the white man had broken up the communal life, which was on a high plane, for the penalty of violation of any of the virtues was death.

The World’s News, Wednesday 3 June 1936

ABO. DIGGERS ACCORDING to a survey of the and activity of full-blooded aborigines in Australia, recently made by the Commonwealth Statistician, eight full blooded abos. served with the A.I.F. in the Great War. How many of those dusky Digger’s are still on deck? One is living in retirement at the settlement on Moreton Island (Q.), but what are the remainder doing? The most prominent abo. Digger of all was Douglas Grant, the only abo. to attain the rank of sergeant…

The Scone Advocate, Friday 23 April 1937

An Emblem of Remembrance. From ‘The Record,’ .the’official organ of the N.S. Wales Division of the Australian Red Cross Society, we take the following article, the person referred to in which is no doubt Douglas Grant, who is still well remembered by not a few friends up the Hunter…

AN EMBLEM OF REMEMBRANCE.

At the end of a musicale given to some of the soldier patients at the Mental Hospital at Callan Park, the artists were amazed when a small dark man came forward to thank them. He made a very charming little speech, in excellent English and delivered with a very nice accent. Then they were told that this man; was an aboriginal of Queensland, who had been abandoned by his parents and brought up by a country family, who had given him a liberal education, and he was a qualified draughtsman. Later in the afternoon, at the visitors’ request, the small dark man took them down to inspect the Shrine of Remembrance he had created in memory of his fallen comrades, a circular pond of cement with two pillars at each side, spanned by a suspension bridge… At each side of the bridge were the dates of the beginning and ending of the Great War, and under the bridge the water flowed — signifying the lives that had passed beneath that bridge during those years. What more fitting token of remembrance to their fallen comrades could there be than this Shrine conceived by a patient and set in the beautiful grounds tended by the patients? The beauty of the thought and the beauty of the surroundings gave a happy feeling in the midst of so much suffering.

Cairns Post, Friday 26 January 1940

Douglas Grant, an aborigine born in the Atherton district, was taken to New South Wales and sent to school. He was a full blood. The writer knew him for many years. In 1930; he saw the writer off at the steamer in Sydney when leaving for Townsville. For six years Douglas was a draughtsman at Mort’s Dock, Sydney. He served in the Great War, was a prisoner of war in Germany, was repatriated. For three years he was secretary of the Returned Soldiers’ League in Lithgow, New South Wales. Then later he worked at the Water Board, Sydney; when retrenched, during the depression he got employment at the Museum, Sydney. He died a few years ago.

Mirror (Perth), Saturday 8 January 1944

Diary Beside Skeleton SYDNEY, Today: with an entry reading “Have had nothing to eat for 10 days, am very lonely, would love someone to speak to” a diary was found beside a skeleton found in a bush cave at Springwood yesterday. Police believe the man starved himself to death. He was Henry Sneddon Grant, 52, [the foster brother of Douglas Grant] former taxidermist at Sydney Museum, who was greatly upset by the death of his wife two years ago. He was given leave of absence from the museum last year and is believed to have been under treatment for nervous trouble.

Northern Star (Lismore), Wednesday 12 January 1944

STARVED IN CAVE: LEFT £1980 SYDNEY, Tuesday. – Henry Sneddon Grant, 52, a taxidermist of the Australian Museum, whose skeleton was found in a cave at Glenbrook last Friday, left property and money worth £1980. This was disclosed at the Penrith Coroner’s Court to-day when the verdict was that Grant had died from starvation while mentally deranged. A diary found by the side of Grant read : “For the past two years life has been a tragedy for me. A doctor gave me a series of injections, which collapsed my brain. Death would be preferable to this work. Good-bye to this tragic world. I have had nothing to eat for five days.”

Nepean Times (Penrith), Thursday 13 January 1944

DECEASED MAN’S DIARY A SKELETON found in a cave at Glenbrook on 7th inst. was identified as that of Henry Sneddon Grant (52), a taxidermist of the Australian Museum. The district coroner (Mr. C. J. Welch), at an inquest held at the Penrith Court House on Tuesday returned a verdict that death was due to starvation while deceased was mentally deranged. It was disclosed that deceased left money and property valued at £1980. Ian Kenneth Grant, of the R.A.AF., stated that deceased, a widower, was his father. Witness’s mother died on April 3, 1941. His father owned a house at “Strathspey,” 29 Ethel St., Eastwood. It was between 16 and 17 months ago witness last saw his father. Deceased’s nerves were then not too good. Prior to that deceased went to see a doctor in Macquarie Street.

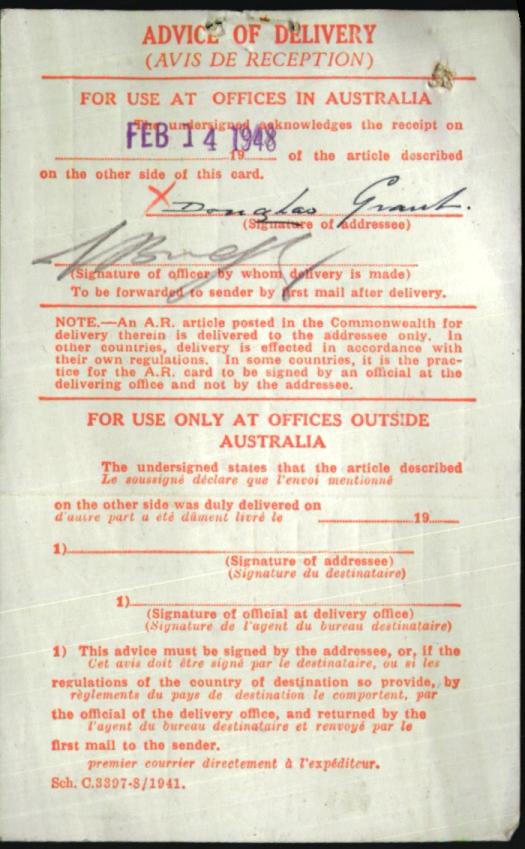

He received treatment. When witness saw him most of the time deceased was quite normal, as far as witness could see, and then he would get depressed. “I noticed the change in him immediately my mother died,” said witness. “My mother was killed in a railway accident. From then on deceased’s mental condition became worse…” A diary and two letters written by deceased that had been found alongside the skeleton were shown to witness, who read them to the court so far as they were discernible. “I say that what my father has written was more through hallucinations than there being any truth in the allegations,” said witness referring to certain passages in the diary. “He never at any time suggested to me that he might take his own life. On the whole he was very much attached to me and my brother.” Douglas Grant said that he was a foster brother of deceased.

In August he and deceased went to Albury. They stayed at a hotel for two days and then returned to Sydney. On arrival at Strathfield they left the train and tried to get accommodation at a hotel there, but failed. They returned to Strathfield station. During discussion an argument arose and deceased left witness on the station and went away — witness could not say in what direction. Witness had not seen him since. As a rule they got on very well together. Deceased was not of a quarrelsome nature. Detective Sergeant Boswell stated that about 1.30 a.m. on Jan. 8, accompanied by other police, the Government medical officer (Dr. Barrow), and the Penrith district coroner, he went to a gully near the Glenbrook railway station, and in a cave there he saw the body of a man… The body was naked, lying face downward on a rug and some other material. Unless a person were to look right into the cave it was possible that he would not see the body.

There was 71/2d in the cave. There was also a writing pad, with writing thereon, and various other writings on paper underneath the body… Constable Stewart, Springwood, stated that he was present, on January 8, when the body of deceased was examined by Detective-Sergeant Boswell and others in a cave at Glenbrook. Witness also saw the body. He identified it as that of a man to whom he had spoken some time previously near Glenbrook railway station. Witness spoke to him on July 8 and 22, 1943. He told witness his name was Harry Grant on the first occasion witness spoke to him, that he was camped under a rock across the Glenbrook railway station, that he had been employed at the Sydney Museum for some years, that he had recently suffered a nervous breakdown, and that they had recently given him three months leave of absence… “On July 22, ,1943,” said Constable Stewart, “I again saw him near Glenbrook station and asked him if he was still camped there. He replied, ‘Yes.’ He was still then in the same untidy condition and had not had a shave… He had a loaf of bread in a parcel when I spoke to him. He did not then give me the impression that he was suffering from malnutrition. He did not say how long he would be likely to be staying there. I think he said he had been there ten days or a fortnight when I spoke to him.”

The Mail (Adelaide), Saturday 12 February 1944

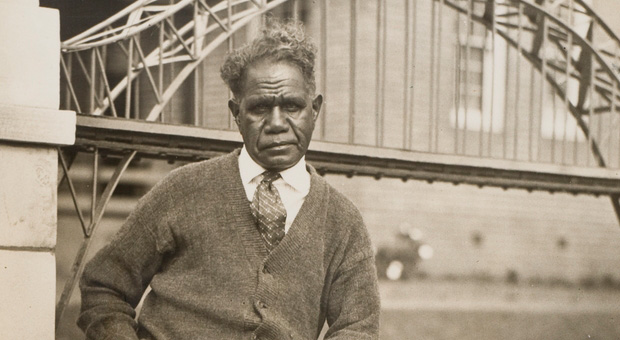

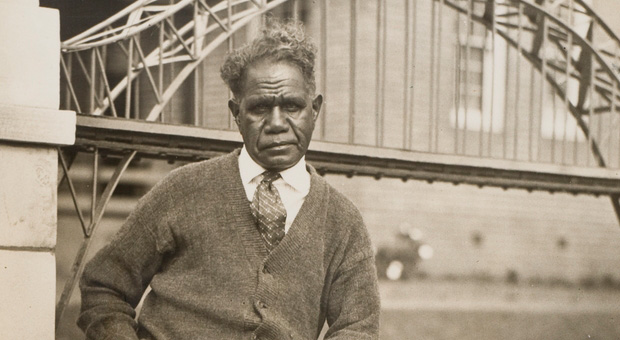

Pure Aboriginal Reared As White Man SYDNEY. — Fifty-six years ago Australian Museum taxidermist Robert Grant found in the North Queensland bush a small full-blooded aboriginal boy whom Grant took home, formally adopted, and christened Douglas Grant. The boy’s parents had been killed in a tribal battle which Grant had witnessed. When, four years later. Robert Grant had a son, the white infant grew up to accept the aboriginal boy as his natural brother. Today, slightly built Douglas Grant is 60, stooped, grey-haired. The lines in his dark forehead deepen, and there is melancholy in his deep-set eyes when he speaks, with a soft Scottish burr, about his race. This week he is in Sydney, following the tragic death of his white foster-brother Henry Sneddon Grant, who was found starved to death in a Blue Mountains cave.

He may take a job at a large Sydney factory. For years Douglas Grant, who is a mechanical engineer by trade, has worked at Lithgow, where he was secretary of the Returned Soldiers’ League, has missed only two Anzac Day marches since World War I. He served with the first A.I.F. in France, was a prisoner of war two years in Germany. During that time the Grant family in Sydney sent him £1 a fortnight to buy small luxuries. Shock for Englishman Once in London, a portly visitor to a soldiers’ reading room went up to the “dark chap” and asked. “You readee paper? Very goodee, ah?” Douglas Grant, nonplussed for a moment, answered: — “If you wish to speak to me, would you please use the proper English, so that I can understand you?” A living example of what can be done with the reasonably intelligent aboriginal.

Grant’s hope and aim today is that Australian aborigines be given full rights of citizenship and full education. “Australia is the aboriginal’s by birth — the Australian’s by adoption,” he says. “The too-amenable, too easily pleased aboriginal did not realise the significance of what he was doing in signing away his land. Surely after 150 years the Government can see its way clear to uplift and emancipate the Australian aboriginal.” Grant does not condemn white Australians for their treatment of his race. “They’re just thoughtless, that’s all. They need someone to make them more aborigine-conscious, to remind them of their obligations.”

Happy Schooldays Douglas Grant says his boyhood was happy at Lithgow and Annandale (Sydney) Public Schools, where the children of his generation — “they were more congenial and homely than children of today” — accepted him without qualms. “They never left me out of any thing. If there was a party on. I was always taken along, too.” Grant is in complete agreement with the law which forbids liquor to aborigines. “When the aboriginal has been educated — when he can distinguish right from wrong, and knows when to stop — then he can take it. Not before,” he says, and adds the phrase he uses most frequently. “You quite understand me?”

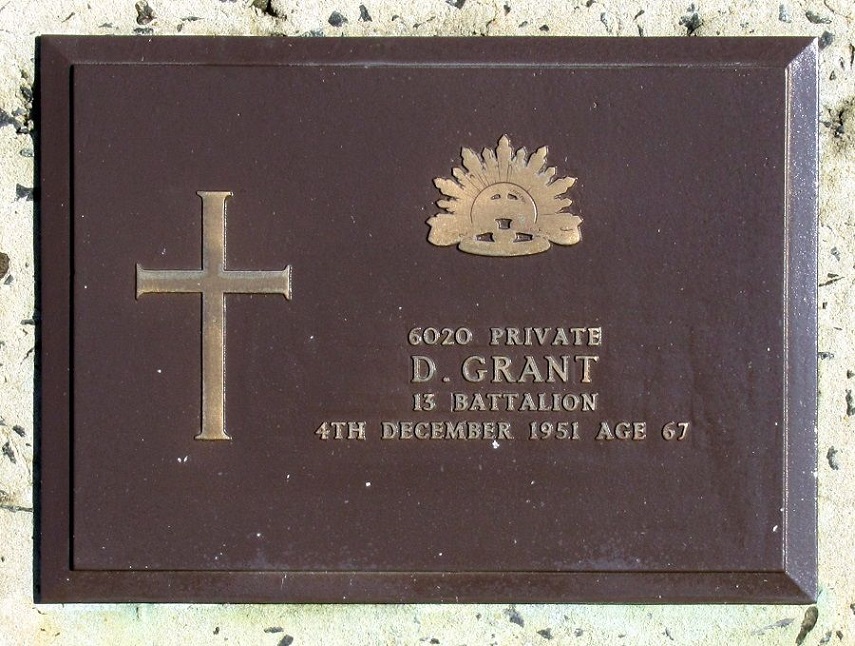

The Gloucester Advocate, Tuesday 8 January 1952

Native Who Made His Mark Dies A full-blooded aborigine who had a splendid record as a soldier in World War I., died in La Perouse War Veterans’ Home. He was Mr. Douglas Grant (65), engineer’s draughtsman, formerly of Lithgow. He had been in the home for two years…

The Scone Advocate, Wednesday 16 January 1952

DOUGLAS Grant (55), who died in Sydney the other day, was no ordinary man. In fact, he was a very extraordinary character. He was an abo. who, throughout his life, was an example to his fellow men, be they black, white or brindle. Moreover, he was a living testimony of what some abos could do if given a chance. Back in the 80’s, during a police raid on an intractable band of abos, the latter retreated and left a squalling youngster behind. A Scots man, Harry Grant, adopted the young fellow, educated him, and then allowed him to join the First A.I.F. After serving in Gallipoli and France with the 13th and 34th Battalions, the young darkie was captured by the Germans, and exhibited in Berlin as a rarity. After the war, the lad visited Harry Grant’s relatives in Scotland, and, on his return to Australia, resumed his job as a draughtsman at Mort’s Dock, being finally transferred to Lithgow. Grant, who spoke with a Scottish accent, was a brilliant scholar, a smart dresser, an interesting conversationalist, and a credit to the man who raised and trained him.

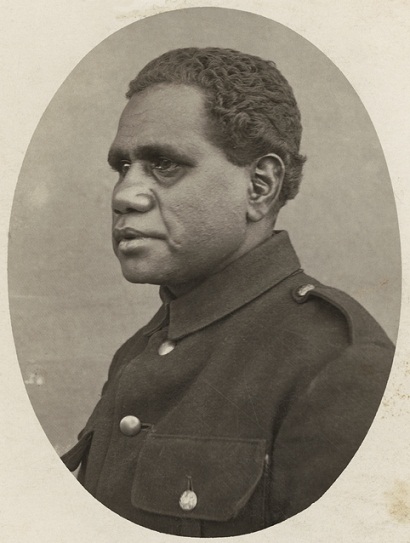

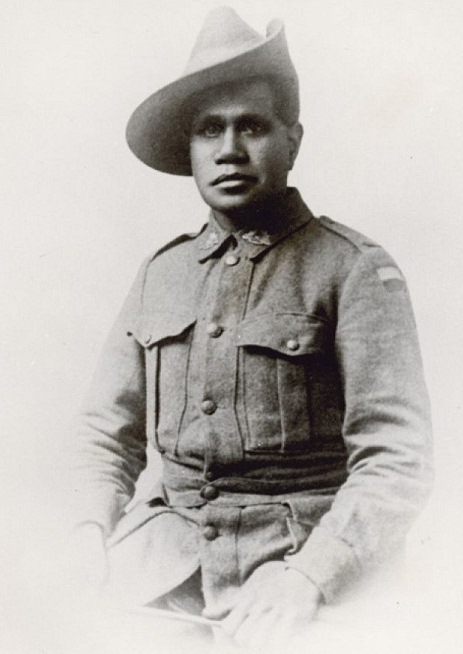

(AWM. NAA photos)